Readers, I could hardly call this Substack a bastion for acute cultural comment, if I failed to address (even just in passing here, in our introduction) the performance Celine Dion recently gave at the opening ceremony of this year’s 33rd Summer Olympic Games in Paris, France. What a performance it was! Like no doubt many of you, I too shed more than one tear over her take on Marguerite Monnot and Edith Piaf’s timeless (1950) ballad “Hymne à l'Amour,” though, perhaps notably unlike many of you, I was not shedding any of those tears over the personal story backdropping Dion’s performance with the frustration and grief of the debilitating disease she is now publicly facing, as explained in her documentary I Am: Celine Dion (Taylor [dir.]) earlier this year. No, readers, I’m not setting myself apart from you here because I’m a monster, coldly shrugging off the reality of that disease and its inevitable and clear effect on the career and life of one of our time’s most celebrated and popular singers; rest assured, cultural commentary has not robbed me of all sympathetic human feeling. No, I actually just had no idea at all at the time of Dion’s performance about her documentary or her disease. Unaware, my tears were instead shed purely for an artist at the peak of her game, delivering a thunderous ballad with all the peaks and valleys of vocal lightning not just her instrument could muster but moreover her song choice required — yes, “required.”

For those of you who don’t know, “Hymne,” like so many of the Piaf’s other signature songs (e.g., “Cri de Coeur”, “Padam, padam…”), resonated so strongly with her contemporary audiences, because it also seemed to come unfiltered and raw straight from the the singer’s beating chest. That beating authenticity was perhaps never as potent for Piaf as with “Hymne” in particular, whose lyrics she herself penned as an enduring lament over the loss of the love of her life, French boxer Marcel Cerdan, to a plane crash among the Azorean mountains in the fall of 1949. The history of that song, then — in not just its performances by Piaf, but moreover its origins for the mid-century French singer — makes “Hymne” no frivolous ditty for any would-be chanteuse to copy, like any reliable classroom recitation, but instead a vocally and emotionally tall order for any who’d attempt to perform it after Piaf to represent the piece with no less equal fervor and feeling than what she originally gave. Even for a singer of Dion’s unquestioned caliber, achieving that standard is not a given, especially not in any single performance; for, just as any world-class gymnast may fail a familiar high-bar routine with a fall or any world-class runner may miss a finish line for a stumble, so too can any world-class singer, even one who is ready to meet the vocal and emotional demands of a song like “Hymne,” fumble or fail performing it for any of many little to large reasons. So, as Dion’s voice clearly radiated out from the balcony of the architectural heart of Paris with what was ultimately a practically perfect reading of Monnot’s music and Piaf’s lyrics and thereby brought to its culmination the already thematically strong opening ceremony, dedicated to the living histories of the Olympic Games and of the French people, among whose number Piaf is still undoubtedly among the first to come to mind for exuding, as Marlene Dietrich so memorably comments in Olivier Dahan (dir./wri.) and Isabelle Sobelman’s (wri., 2006) La Vie en Rose, “the soul of Paris” (see clip here), I couldn’t but fully emotionally cave, in sincere appreciation of this truly great work of art, actively connecting culture with strength and past with present while passing over and through not just me, nor even just the Games, but also the entire city of Paris and from there the entire viewing population of the world, whose own personal and national interests I can only imagine from the social media posts over the days that followed also faded in awe of the passion and power (healthy or not) Dion’s voice gave to Piaf’s words and to the Games themselves — and live! no less — over the ascending Olympic flame. “Wow,” indeed, Mike Tirico.

And that, readers, is why I cried: not over Dion’s failing but seemingly indomitable health, but rather over Dion’s triumphant and persistently powerful artistry; and that, readers, is what I hope Celine knows we in her audience ultimately applaud: not just her well-remembered performing and recording legacy, but moreover her present and on-going work to bring new peak performances to us from the stage. Bravissima!

Alright, that performance addressed, readers, let’s get on with the show.

Fantasmas (Limited Series)

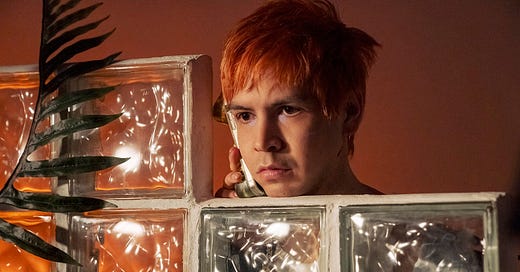

Max • Comedy • Windmillinery

Synopsis

The loss of an oyster-shell earring sets a self-mythologizing New Yorker onto an odd series of departures from all responsibility in a persistent attempt at its recovery.

My take

After the niche success(?) of his film début Problemista (2024), comedy writer-director Julio Torres, whose top credits remain his sketch work for Saturday Night Live (SNL; Michaels [creator], 1975-present; see “Papyrus” [2017] and “Wells for Boys” [2016]), apparently found corporate investment enough to follow up that film and his curious if Peabody-winning series Los Espookys (Torres, Fabrega, & Armisen, 2019-2022) with a new elaboration on the self-mythologizing fiction he had invented especially in Problemista. Just as “defiantly original” (Peabody, 2022) as those earlier works, this new series reproduces the blameless undulating charm Problemista represented, only now with the decidedly darker edge Los Espookys favored. Thus a kind of fever dream whose nearest cultural relatives are likely:

the queer affected cinema of the 1990s and early 2000s (e.g., Trick [Fall (dir.) & Schafer (wri.), 1999], But I’m a Cheerleader [Babbit (dir./wri.) & Peterson [wri.], 2000]),

absurdists’ social commentaries with roots in Molière (e.g., I Think You Should Leave with Tim Robinson [Robinson & Kanin (creators), 2019-2023]; see my take on its third season here), and

those bizarre circumstantial faux sitcoms that the Cartoon Network airs at three in the morning (e.g., Eagleheart [Koman & Weinberg (creators), 2011-2014]),

Fantasmas is the eccentric brand of soda water no one needs to drink or even tries to purchase outright, but somehow still survives, beguiling shoppers with its haunted ubiquity on shelves and in friends’ refridgerators domestic and abroad.

Now, for me, who friends will know dislike the tacky zing of any carbonated water, this particular brand of art-pop isn’t an undeniable win. Sure, there are passages in Fantasmas that contrive and surprise in sensationally pleasant if culturally anarchical ways (e.g., Aidy Bryant’s cameo commercial for toilette couture); but overall the persistent effect of Torres’ twee peculiarities tires more than inspires the senses. While I dare not directly apply the word “quirky” to the series for fear of critical reprisal replicant of Rose Matafeo’s irked rebuke of the term as insidiously reductive on Max’ once stellar Starstruck (Matafeo [creator], 2021-2023); see my take on its second season here), I don’t know how else to efficiently describe the 100%-taste-based appeal (or distinct lack thereof) Fantasmas simply will or won’t emanate for you as a viewer in its audience. The best I can do here is (1) note emphatically how sincerely you, if at all curious about the series, should give it a try and (2) simultaneously remind you (and everyone) that the series’ value as a quir— nope, I won’t do it — quixotic cultural comment remains, sadly, only as outstanding as:

any Todd Solondz film,

sci-fi Are You Afraid of the Dark? escapade (MacHale & Kandel [creators], 1990-1996, 1999-2000, 2019-2022),

camp SNL sketch (e.g., “The Real Housewives of Disney”), or

midnight bezoar horror-comedy-fantasy (e.g., Eagleheart S2E02)

doesn’t already exist within our culture.

Temperature check

Tepid (just barely)

Lady in the Lake (Limited Series)

Apple TV+ • True Crime • Midcentury Mishpocha

Synopsis

The sudden disappearance of a local Jewish girl triggers the survival instincts of an otherwise overridden housewife in her community, at the same time as a thanklessly responsible Black mother confronts an implicit choice between personal dignity and material welfare on the fringe of organized crime.

My take

In one way perhaps The Lady in the Lake is the best television series Apple TV+ has ever produced. Like any good “true crime” podcast, its narrative succeeds to the greatest extent in casting its lure: We in the audience are coaxed willingly into its thrall, which with a thick veneer seductively shrouds what we all know will ultimately be a delicate but devastating revelation. Perhaps were it not for the twinkling beauty of that lure, we could feel ourselves clever enough to look away; but something about the grace with which it dances in the water, an enigma slowly undressing itself before our gaze as would an unbloomed flower strip itself petal by petal to reveal a somehow magical core (think the “pollination scene” from Bennett and Huettner’s Scavengers Reign, 2023), keeps us transfixed. If only to let ourselves be so fascinated, we watch such unfolding finesse unflinchingly, carelessly ignoring the ripples and wake in the surrounding waters. Are we predator, readers, or are we prey?

To linger in that metaphor is to exalt The Lady in the Lake for nearly the only true quality it actually does possess; for, beyond a convincing lure, it is certainly not the rest of the writing — i.e., the story or the way that story is presented — that keeps anyone’s praise for the series high. We’ve already seen plenty of stories like this one before (e.g.,

Gone Baby Gone [Affleck (dir./wri.) & Stockard (wri.), 2007];

The Outsider [Price (dev.), 2020];

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo [Fincher (dir.) & Zaillian (wri.), 2011];

The Hours [Daldry (dir.) & Hare (wri.), 2002];

If Beale Street Could Talk [Jenkins, 2018]

), and clunky omniscient voice-over as a storytelling device is exactly as Brian Cox’ terrific character, Robert McKee, in Charlie Kaufman’s fabulously antithetical and self-consciously solipsistic Adaptation (Jonze [dir.] & Kaufman [wri.], 2002) proclaims:

God help you if you use voice-over in your work, my friends! God help you! It’s flaccid, sloppy writing. Any idiot can write voice-over narration, to explain the thoughts of a character.

Yes, readers, perhaps unusually, what quality there remains in The Lady of the Lake after its alluring introduction is actually in the authenticity of the world it provides its player inhabitants. Both literally and tonally, this world has an outstanding design, including interiors AND interpersonal dialogue so redolent of a specific time and place that one may need to check one’s calendar to actively remember that there hasn’t been any real transportation. Of course, the make-up and costumes contribute to this illusion, but for me it’s truly the vicious dialogue between pairs of characters, that smacks of real — even hauntedly real — conversations among ambivalently antagonistic and authentically individual people. Perhaps this impressive verisimilitude is originally the work of Laura Lippman, writer of the novel on which the series is based; but, even if so, it remains a credit to the adapting talent of especially the series creator, Alma Har’el, that that original dynamism isn’t lost in translation from page to screen.

Whether the series ultimately proves worthy of the investment will remain a question answered only after this month, when it concludes its mystery, but for now I’m at least pleased enough with what it’s shown to register a stable:

Temperature check

Tepid

Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes (2024)

Hulu / Disney+ • Science Fiction • Pastoral Patrioteering

Synopsis

The heir apparent to the leadership of a tribe of mild-mannered falconers fights to understand and then preserve its way of life in a rapidly competitive world.

My take

Like its predecessors (viz.,

Rise of the Planet of the Apes [Wyatt (dir.), Jaffa, & Silver (wri.), 2011];

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes [Reeves (dir.), Bomback, Jaffa, & Silver (wri.), 2014];

War for the Planet of the Apes [Reeves (dir./wri.) & Bomback (wri.), 2017]),

Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes is a spectacle by effects experts for effects experts. The technical work involved in creating, moving, and correctly lighting the main characters in the film, nearly all apes of various kinds, is impressive, even after the now three prior films featuring similar work. No doubt this film will be in contention, just as those predecessors were, for the year end’s Visual Effects awards at the Oscars and other ceremonies.

Effects aside, the rest of the film is adequate, I suppose. Thirteen years into the current franchise’s run, 56 years since the original film’s début, and 61 years since the publication of the entire legacy’s source material, my expectations for what any new Planet of the Apes installment will bring are both low and predictable: Surly, often spiritual tribalisms drawn along inter-species lines slowly but assuredly give way to a more inclusive respect for sentience, whatever the body, amidst a post-apocalyptic landscape simultaneously as primitive as it is littered with at least the remnants from a predeceasing but technologically cutting-edge society. (The screenwriting for this series is practically formulaic at this point.)

What remains to be seen in any new Planet of the Apes film is an unambiguously strong director’s point of view on that relatively rote material. After the Maze Runner series (Ball [dir.], Oppenheim, Myers, & Nowlin [wri.], 2014-2018), Wes Ball I feel sure won’t be that director; but — stepping away from this film for a moment, to focus on hopefully brighter things — with any luck he’ll become that director, if not for a future Apes film, then at least for a confident adaptation of Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka’s (1986-present) The Legend of Zelda next year (see Nintendo, 2023).

Temperature check

Cold (unless you love VFX)

The Boyfriend (Season 1)

Netflix • Reality • Coffee Dates & Roommates

Synopsis

Single men coöperatively run a coffee truck while considering each other for long-term romance in Japan.

My take

Readers, as you well know, I don’t typically write about reality television here. Though I certainly still watch many versions of it (from Survivor [Parsons (creator), 2000-present] to Love Is Blind [Coelen (creator), 2021-present]), long has it been since any new entry into the genre caught enough attention and carried enough merit to make mention of it here. Netflix’ new The Boyfriend, however, with its unusual mix of sexual politics and cozy commentary, I think, is worth the words.

Perhaps the first gay dating show ever native to Japan, a nation where same-sex marriage and even same-sex civil unions remain widely illegal (despite some recent rulings of unconstitutionality this and last year regarding their bans), The Boyfriend is uniquely at the crossroads of (1) a still pending acceptance of LGBTQIA+ people in a highly traditional society and (2) the ever-broadening interest in reality dating shows, now encompassing people at all points in the sexual orientation spectrum around the globe. Therefore following in the footsteps of, on the earlier side, Boy Meets Boy (Bravo, 2003) and A Shot at Love with Tila Tequila (McCormick [creator], 2007) in the U.S. and, on the latter side, The Ultimatum: Queer Love (Coelen [creator], 2023) and Love Is Blind: Japan (Coelen [creator], 2022), The Boyfriend is somehow wise and sensitive enough in its socio-sexual naïveté to allow the housemates’ authentic experiences to take center stage, even while its producers still provide the requisite companionate incentives and situations to nudge connections, both fraternal and romantic, along: The men reveal their insecurities and fears about their identities especially within the society they call home, support each other even as some become rivals in love, and still foster genuinely entertainingly dramatic entanglements that feel at home within the present landscape of reality dating shows, wherein perceived slights and audacious confessions incite conflicts and communions with equal excitement.

And, though I initially found it odd, what I’ve come to understand is almost a staple in Japanese reality television, the panel of commentators to whose opinions and conversations the editors flicker back and forth with the footage from the house, celebrates the cozy quality of the series. Watching with the commentators feels like an enhanced experience, where you with your cup of tea on the couch at home fit right into a cohort of simultaneous viewers and thereby find more than just the main story to reflect on or reäct to.

Will the series be critical and commercial success? It remains unclear. How much the widest audience will want to watch a fairly niche reality series about relatively timid, if attractive, gay men is a question I’d hesitate to answer with any gusto. However, even if only a fraction of the society into which this series was originally born could see and empathize with the emotional honesty these young men bring to their televised experiences, I’d consider the show a success. As Dustin Lance Black (wri.) had Harvey Milk say in Gus van Sant’s (dir.) excellent Milk (2008), “they vote for us two to one when they know they know one of us.” Here’s hoping, Japan.

Temperature check

Hot (and cozy)

Those About to Die (Season 1)

Peacock • Drama • The Whip Hand

Synopsis

Contests over ownership rattle all tiers of ancient Roman society, from the imperial palace to the sands of the arena.

My take

A befitting title recognizes the breadth and depth of this new drama, focussed on the diverse lives of people in ancient Rome. Seemingly designed to attract as many Spartacus (DeKnight & Raimi [creators], 2010-2013) fans as Spartacus (Kubrick [dir.] & Trumbo [wri.], 1960) fans, the title describes the series to be not just a visceral depiction of the events of the ancient Colosseum, but moreover a lamentable depiction of the events of the late Roman empire and the choices that led to its ultimate demise. Living up to that multifaceted description, Those About to Die is as much a spectacle as it is a eulogy; and for me Hopkins’ presence on the cast is as good a signifier as any, that both components are indeed present there with a purpose.

Operating in the wake of Milius, MacDonald, and Heller’s (creators) notoriously expensive series Rome (2005-2007), which first tackled a full-fledged recreation of ancient life at scale for a modern audience, as well as in the calm before Ridley Scott’s increasingly anticipated Gladiator II (Scott [dir.], Scarpa, & Craig [wri.], 2024), whose own predecessor (i.e., Gladiator, 2000) reinvigorated the concept of ancient life for a modern audience’s fascination, Those About to Die draws no surprises in its portrayal of the Roman Empire — no doubt in order to sit as comfortably within the “Greco-Roman space” on the mainstream (American) palate as those other dramas, that first weaned that palate to care. While the drama at the series’ core updates the degree of node-to-node negotiations from those closest cultural relatives to more closely resemble the headache of multidirectional politics the mainstream (American) palate has developed a taste for of late (i.e., via subjections to ‘ensemble dramas’ rich with competing agenda; e.g., Succession [Armstrong (creator), 2018-2023], Game of Thrones [at least its earlier seasons; Benioff & Weiss (creators), 2011-2019]), the basic contentions remain familiar:

contests for dominance in the arena or under an aging plutocrat,

obstructions to justice or social ascendance for the downtrodden,

personal and sexual ambitions driving paupers toward princely status,

old wounds seeping with unexpected vengeance,

sisterly bonds warming separated souls,

natural disasters clouding common horizons,

champion races circling a central stage,

immigration and (re)patriation, and

even LGBTQ+ romances (in addition to the heterosexual staples)

all intertwine in an almost surprisingly recognizable fashion, given just how many separate ideas the series contains. I suppose, upon reflection, this intelligible cogency despite variety may be the series’ greatest achievement — though honestly we’d hope for more as that greatest achievement than just a kind of dramatic pastiche of favorites past.

Are we not entertained? No, no, we are entertained, readers. It all just feels so edgelessly familiar an entertainment, that we wish life here weren’t all bread and circusses.

Temperature check

Tepid (weakly)

Wicked Little Letters (2024)

Netflix • Comedy • Foxy-assed philately

Synopsis

A rash of defamatory missives ignites a personal dispute between a catechismic spinster and her libertine neighbor.

My take

As fun as it may be to — spoiler alert — watch Rich Pick and Oscar and Emmy winner Olivia Colman tell off nearly everyone who breathes in her vicinity in the filthiest language her character’s puritanical mind can muster and as good as it may be to see fellow consummate British actors including Timothy Spall, Gemma Jones, and Eileen Atkins come together with Colman for such a lighthearted project, Wicked Little Letters’ paper-thin story and screenplay, a milquetoast ‘whodunnit’ for semanticists on the order of Ella Minnow Pea (Dunn, 2001), contrives little more humor than a third-grader’s first taboo dashes into “colorful” language. The film so badly wants to appeal like Chocolat (Hallström [dir.] & Nelson Jacobs [wri.], 2000), a similarly pastoral tale about taboo-breaking and liberation, but simply doesn’t allow for charm to bake in long enough, so to speak, to have the audience taste much upon sampling. Colman’s Bible-cleaving protagonist and Jessie Buckley’s bottle-wielding antagonist are so diametrically opposed in manners and expectations from the very prologue, that most audience members would struggle, I’d wager, to connect with either of them or their conflict. Without connection, there’s little to care about what they do or what they become. So, though Colman for example may play her character perfectly as written, the character itself fails to bring both light and dark enough to encourage sympathy. Really, the only sympathetic character in the piece is a supporting policewoman, whose own secondary storyline is told so far from the heart of the piece, that even when its pay-off occurs we in the audience have been trained to care so little for it that we enjoy it less as the emotional and social win I strongly suspect it was intended to be than as one fleeting entertainment among the many final ties the story offers as resolutions.

Readers, I genuinely wish I had better things to say about this small comedy of manners, because I would have loved for it to be a gem, but it just very much is not a gem, not really anywhere, not at all.

Temperature check

Cold (brr)