Wow, readers, I do feel as if I’ve been nursing this post for the better part of this year; so my apologies first to you all for taking so long to publish it! I cherish you and appreciate the support you all have given by reading, commenting, and sharing my writing on this Substack so far. (Keep it up!)

But, it turns out, what better a time to review the offerings the latter half this 2024-2025 year in television has made than right now, just as the eligibility period for the 2025 Emmy awards has come to an end, with the end of May! So, let’s discuss everything from the few “banner” series likely to compete for the Outstanding Comedy, Outstanding Drama, and Outstanding Limited or Anthology Series Emmys this year to the occasional comedy special and streaming film that has caught our attention over the past five months.

With hope that your cups are ready… 🫖

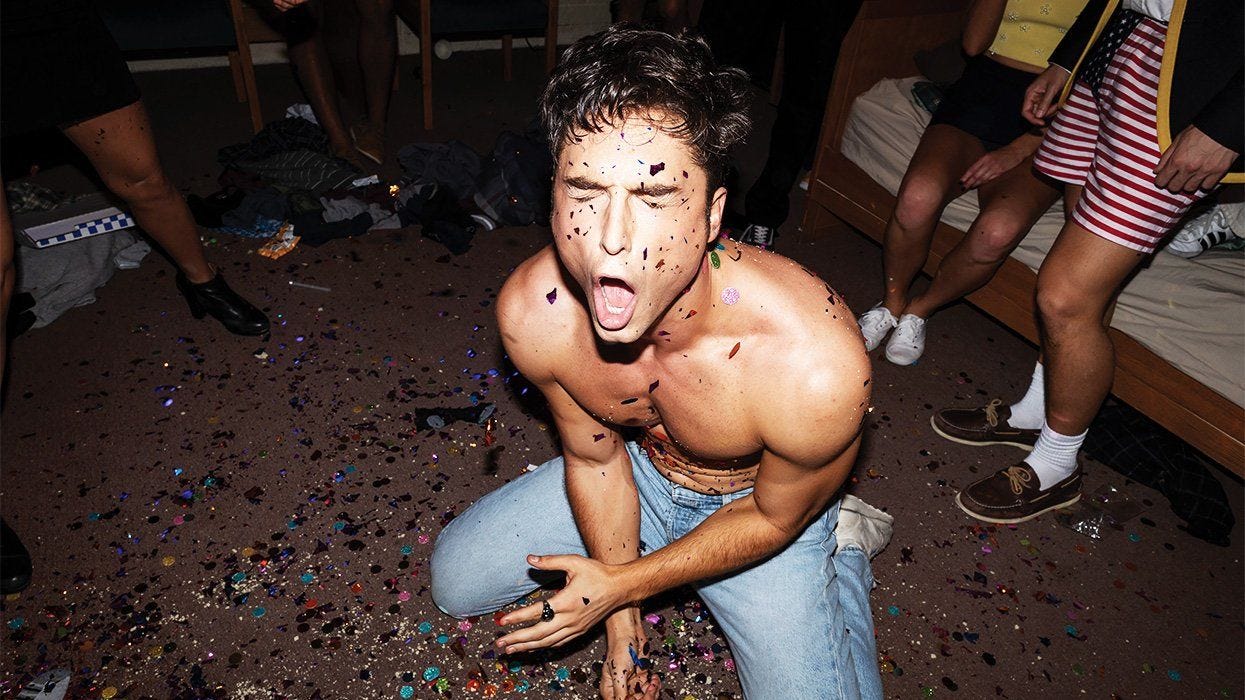

Overcompensating (Series Premiere)

Amazon Prime • Comedy • Masc. Looking

Synopsis

Posturing for popularity starts to feel defeatingly costly for a closeted college freshman and his family and friends.

My take

Take note, writers: *This* is how to do a sex comedy.

What The Sex Lives of College Girls (Kaling & Noble [creators], 2021-2025) might once have briefly had,

what this aptly titled (and surprisingly long-lived) spoof on Dunham’s (2012-2017) Girls definitely had, and

what every studio-produced romantic comedy targeted at adolescents and new adults in the last forty years (if not since Boccaccio’s [ca. 1350] Decameron) hopes it had

is exactly what Benito Skinner successfully brings to the table in this new series about a closeted college freshman repeatedly weighing his desperate self-commitment to “fit in” against his desperate deep desire to let his true self out: namely, wit — specifically:

the wit to trade on the surface in parties, pop stars, and prurience without ever allowing those indulgences for even one second to comprise one’s actual business;

the wit to perform and relish in a(n occasionally literal) strip tease of “good behavior” and other mainstay proprieties while simultaneously sustaining an intelligent discussion of morality, interpersonal politics, and personal authority; and

the wit to actually be funny (rather than merely play at funniness) throughout.

As a result, Overcompensating certainly isn’t just “another teenaged comedy,” but instead like the Gypsy Rose Lee of our current television vaudeville a living model of how well it’s possible to marry a decadent, eye-catching display with a perceptive, thought-provoking social commentary. Such a successful marriage is rare in our culture and, perhaps as a result, powerful. Dare I refer yet again on this Substack to the seemingly limitless power of Darren Star’s (1998-2004) Sex and the City, whose six extended seasons, two feature films, extended merchandise, and currently airing reboot (see my take on the current season of And Just Like That… below) testify to the long-term success any series — but especially a sex comedy — can have when it properly balances its superficial appeal (here, overt sexuality) with an identifiable discourse on especially the subtler challenges of a contemporary social experience? Skinner is clearly a product of, if not student of, that modern standard for comedy writing and, in my book, has penned the most successful successor in that cultural tradition since Sex and the City’s original run, specifically in his work on Overcompensating’s pilot episode. I literally applauded from my couch.

That said, after that all-time excellent pilot, Overcompensating does struggle just a bit to keep its standard flying equally high throughout the rest of its premiere season. Unlike, say, Arrested Development (Hurwitz [creator], 2004-20061), which was able to keep its comedy flying high at sound-barrier-breaking speeds not just for entire episodes but across entire seasons, Overcompensating — perhaps all too fittingly for its not entirely successful protagonist — has flagging eddies, wherein its momentum and its otherwise persistently clever tone wane, usually in service of somewhat underworked plot developments peripheral to the central character. To be clear, these plot developments remain important narrative elements and structurally set up later comedic and dialectic rewards; they just fail to happen with as much streamlined polish as many other equally important but consistently high-flying moments throughout the season. To this end, Overcompensating, at least as far as Skinner and his fellow writers’ work goes, has not yet achieved complete mastery over the same complex interlocking machinery by which present occurrences, already dressed by past parameters, cyclically beget future punchlines and for which Arrested Development famously earned acclaim.

Still, to miss this series would be a mistake in my book, readers. While the standard does never fly quite so high again as it does in the pilot episode, Overcompensating nevertheless delivers on a level of comedy, thanks to its wit, well above the line of nearly every other comedy currently airing. Perhaps it is the keen (and at least semi-autobiographical) authenticity Skinner brings to not only the writing but also the acting for this series, in his central performance of a character he clearly knows so very well, that imbue the episodes with an undeniable charisma and a recognizable empathy that make it hard for viewers not to admire and enjoy what they’re seeing. Or, perhaps it’s my favorite aspect of this series, the wordless background punchlines sprinkled throughout the eight episodes in order to not just break up bigger scenes but also comically characterize a particular time and place, that give the series that remarkable appeal. Whatever it is, even if this new series is just Amazon Prime’s answer to FX’s recent success with Brian Jordan Alvarez’ (2024) English Teacher — i.e., a decidedly more “adult” but still similarly lived-in queer sitcom. — (see my take on it here), Overcompensating *on its own merits* has earned my praise.

Temperature check

Hot!

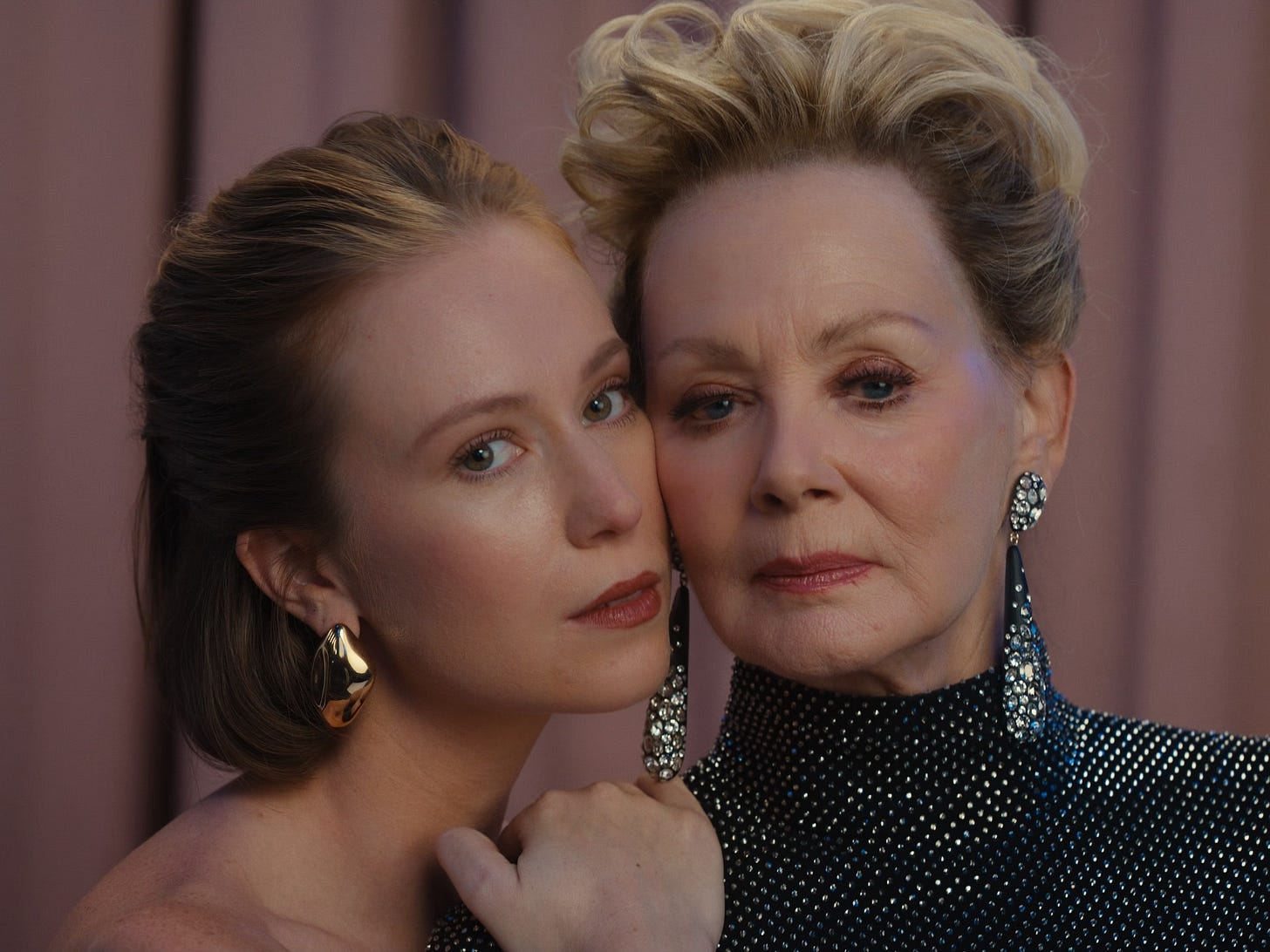

Hacks (Season 4)

Max • Comedy • What’s Old Is New Again?

Synopsis

Feelings of betrayal fuel a feud between a seasoned comédienne and her millennial head writer, who both despite their antagonism desperately want their new late-night talk show to succeed.

My take

Let me be the first to say, how glad I am that the most acclaimed comedy series currently on television has officially returned for its fourth season, after what was a powerful and celebrated third season (see my take on that season here).

However, let me also be the first to say, readers, that the fate of this fourth season seems more precarious than the fate of the last season. Judging by the first two episodes, one of which was a solid but not quite A-level season opener and the other of which was a relatively hackneyed dream-based dramatization of the protagonist’s psychological interior à la last year’s Nightbitch (Heller, 2024; see my original take on that film here), Hacks may be in trouble of averaging just a middling quality this year. It’s not that I didn’t laugh heartedly during both episodes; it’s just that the direction the writers seem to have chosen amounts to a perhaps necessary but still confidence-wounding backtrack on an otherwise daring season premise (viz., the feud, or “confidantes turned adversaries”) that implicitly undoes whatever accumulated interest that premise earned in acclaim and viewership since the third season. It smells of a writers’ room unsure of how to proceed in this new arena, where their and their audience’s two central and beloved characters are no longer comrades in arms with a biting rapport but active frenemies who now trade barbs for personal victories instead of shared laughs. And to draw upon a trope so familiar — i.e., the revelatory dream sequence, in which a natural avatar literally and figurately blocks the protagonist’s path — smells worse: of laziness, or a complete lack of the inventive spirit that has made basically everyone who’s bothered to watch it a fan of this series since its début four years ago. Sure, the necessary expansion of the characters’ scope and of the secondary cast keeps minimal interest afloat in the “new blood” sort of way, but is that all we can expect from this fourth swim in uncharted waters? Hacks was and has been the one place on television we’ve seen a woman over 60 unambiguously succeed as the lead in a “mainstream” comedy, a feat we haven’t even considered socioculturally since Bea Arthur triumphantly led The Golden Girls (Harris [creator], 1985-1991), — and even she was only in her 50s then. Fall back not, Hacks writers, on any simpler a path now than the one you’ve already taken to get you this far, please.

Coda: Having now seen the full season, I am sad to report, they didn’t hear me.

Temperature check

Tepid (sadly)

The White Lotus (Season 3)

Max • Drama • The Oneness of You

Synopsis

Vacationing elites and local staff conflict in Thailand, as the exigencies of the external world encroach on what would otherwise be an idyllic retreat.

My take

What a sincere pleasure it is to once again revisit this highly engineered but completely authentic world created by writer and director Mike White! No one else is writing at his level in dramatic television today, and only Ben Stiller approaches White’s level of skill in the director’s chair (see my take on the recent season of Severance below).

It’s likely White’s strong acquaintance nigh intimate identification with each of the characters he presents each new season of The White Lotus, that makes the watching of it so immensely pleasurable; his adeptness at isolating carefully, with the precision of a technical surgeon, just what a character would do or say in his or her own uniquely curated vernacular in a given situation thoroughly imbues each such situation, however foreign to us in the audience in any of many countable ways (e.g., personal philosophy, literal geography, materiality, fortune, desire, gender, age), with an unmistakable authenticity any cultural scrutinizer would be forced to stamp forthwith with undiminished approval. Of course, it also helps that White’s adeptness extends to his uncanny cognizance of what kinds of expression, among many possible lines of dialogue or story, are the most likely to go viral; one needs only look at the sheer number of times and ways Jennifer Coolidge’s character Tanya especially during and after the series’ second season was (and will likely continue to be) memed for her outlandish and hysterical quips to find the evidence. And then, finding that evidence, one can appreciate all the more White’s ability to walk both sides of that line, between frivolous popularity on one side and cerebral integrity on the other, without diminishing either. The degree to which he not just knows but also adores all his characters, perhaps even especially those most eccentric few including Tanya, keeps the show, despite its obvious tendencies toward wry sociocultural commentary, from steeping so long in any one crevice of criticism that actual ridicule ever arise to the surface. I can honestly say that the sixth episode of this third season is one of the best episodes of television I have ever seen — and I sincerely wish more people would take the time to also acknowledge and see it for that level of quality.

With thanks to:

the creative executives at Max and elsewhere who have wisely given White the free reins to drive and deliver as he sees fit these three seasons of The White Lotus, and to

the creative cast and crew that support his vision so well, especially Leslie Bibb, Jason Isaacs, Parker Posey, and Patrick Schwarzenegger this season each of whom I feel certain is destined for an Emmy nomination (if not win) this summer,

the third season of The White Lotus is must-see television, appealing across genres to the political and cultural zeitgeist of our time and picking ever so cleverly at the façades and performances (of personality, responsibility, masculinity and femininity, wealth, justice, and politics) we perhaps universally recognize and want to reprehend in so much of the mainstream discourse we’re subjected to across the board in our contemporary news and other media. Nowhere else will you see, nor can you see, so fine an artist’s hand portraying the intergenerational sexual, financial, ethical, and literal politics of 2025 and making the effort look and feel so freaking easy. Bravissimo! More is more.

Temperature check

Steaming

The Last of Us (Season 2)

Max • Drama • The Hills Are Unalived

Synopsis

Vengeance festers when sublimated.

My take

It wasn’t until The Walking Dead (Darabont [creator], 2010-2022) showed American audiences that a serial horror story could not just survive — forgive the pun — but moreover succeed on television, that anyone would have bothered even considering, no less actually trying, to produce a dramatic adaptation of a horror video game series like The Last of Us (Naughty Dog [dev.], 2013-2024) for a mainstream audience. Frights and jumps had been OK for one-off specials (think independent episodes of The Twilight Zone [Serling (creator), 1959-1964]) or for singleton cinematic jolts (think Night of the Living Dead [Romero (dir./wri.) & Russo (wri.), 1968]); but episodic narratives, especially multi-season episodic narratives, had been squarely the domain of only “serious” drama.2 That The Walking Dead somehow succeeded anyway — and I use “somehow” critically here, to cite what I expect was the widespread surprise of television executives who could not have seen that success coming — was from that perspective likely just an anomaly, but undeniably a lucrative one: Not only did the main series itself air with high ratings for eleven(!) total seasons — an accomplishment previously known only to monocultural heritage works airing on major networks (e.g., Friends [Crane & Kauffman (creators), 1994-2004], Frasier [Angell, Casey, & Lee (creators), 1993-2004]) — but it also spun off several connected series, a few of which continue to air today, and a host of extended media (e.g. books, video games) also sharing in the intellectual property. Consequently, to the extent that any of the same undercurrent of doubt about the commercial and creative viability of an otherwise reputedly short-term (vs. long-term) entertainment genre persisted in television studios and production houses even after The Walking Dead’s established success, it should have come as no surprise that, if any series were to “get the green light” to follow in the footsteps of that “anomalous” horror series, it would be none other than a second zombie series, at least superficially cut from the same tattered cloth; after all, from a financial perspective, what better a “risky” bet to fund than the one with an already proven history — not just on television, mind you, but also in the cross-media world of video games (where The Last of Us has sold more than 37 million copies to date)? My point, readers, is that, when thinking about and digesting The Last of Us, the question wasn’t ever, will it succeed?; no, its cultural predecessor’s success and its own source material’s success obviate that uncertainty. The real question for this series has always been instead, will it sustain its initial success beyond its début season and, if so, how?

Happily for The Last of Us, as it was for the last dramatic adaptation HBO Max held aloft for years, the preëxistence of material not conditional upon the whims and exigencies of a working television writing room has meant a path paved with as much fortune for the audience as there is misfortune for the characters: Narrative events aren’t beholden to actors’ contracts or a studio’s interests, but to the frequently violently dramatic plot points of the video games’ source material, plot points that — spoiler alert — don’t care if you had top billing during Season 1 (translation: you’re still expendable); and this predestined quality to the storytelling has allowed the second season to have a level of security in finding its footing both the writers and the audience can feel reässured by. Resurgent animosities, real and imagined, build upon the prior season’s woes and connections effectively, challenging the central characters to confront their limits, whether those limits be emotional or physical in nature; and the results of those challenges become the stuff of great serial drama, binding together what otherwise would be just stretches of uneasy quietness separating bursts of violent action (e.g., when the unnatural world attacks) to intentionally color the plot. The long-term challenge for the series then has been and will remain (1) how to qualify that binding with enough authentic attitude and self-respect, to not compromise its load-bearing structural integrity just for the sake of viewership, and (2) where and how to proceed once that narrative predestiny is exhausted. While the latter of these two questions remains one yet to be answered by seasons after the second, for now we can examine The Last of Us for substance on the earlier point.

There, the biggest comment I can make on the second season of The Last of Us is a lament: If only Bella Ramsey were a better actress… Yes, while Ramsey’s disaffected indolence felt an appropriate global immaturity for her twelve-year-old character during the series’ first season, this second season requires her performance to mature and diversify just as her character does over a span of five years; and Ramsey just doesn’t seem up to the task. Romantic interludes, frightful responsibilities, and remnantly a headstrong petulance call for an emotional depth Ramsey’s character must visibly mean to bury yet simultaneously declare a readiness to master. Thankfully, the complex wordless exchanges with her primary scene partner, Pedro Pascal, can lean on his skills at subtly conveying the emotional complexity his own character requires in their fraught but limited dialogues — and for that work he feels destined to compete for the Outstanding Lead Actor Emmy this year (in whatever category — Drama or Limited Series or Anthology — the Television Academy decides this second season best fits within, because of its shorter-than-eight-episode duration). Still, the lack of a complete reciprocity between his character and Ramsey’s undercuts a great deal of the dramatic richness the season and the series might have otherwise enjoyed.

At least we can be thankful the series has welcomed Catherine o’Hara to the cast this season. Her top-tier dramatic acting achieves all the rich nuance the ostensibly spare script wishes her character, like every other centralized character, would embody. Though commonly thought of as a brilliant comedienne (thanks most recently to her Emmy-winning performance in Levy and Levy’s [2015-2020] Schitt’s Creek), o’Hara represents the best of the best in the drama fueling this altogether lukewarm second season.

Temperature check

Tepid

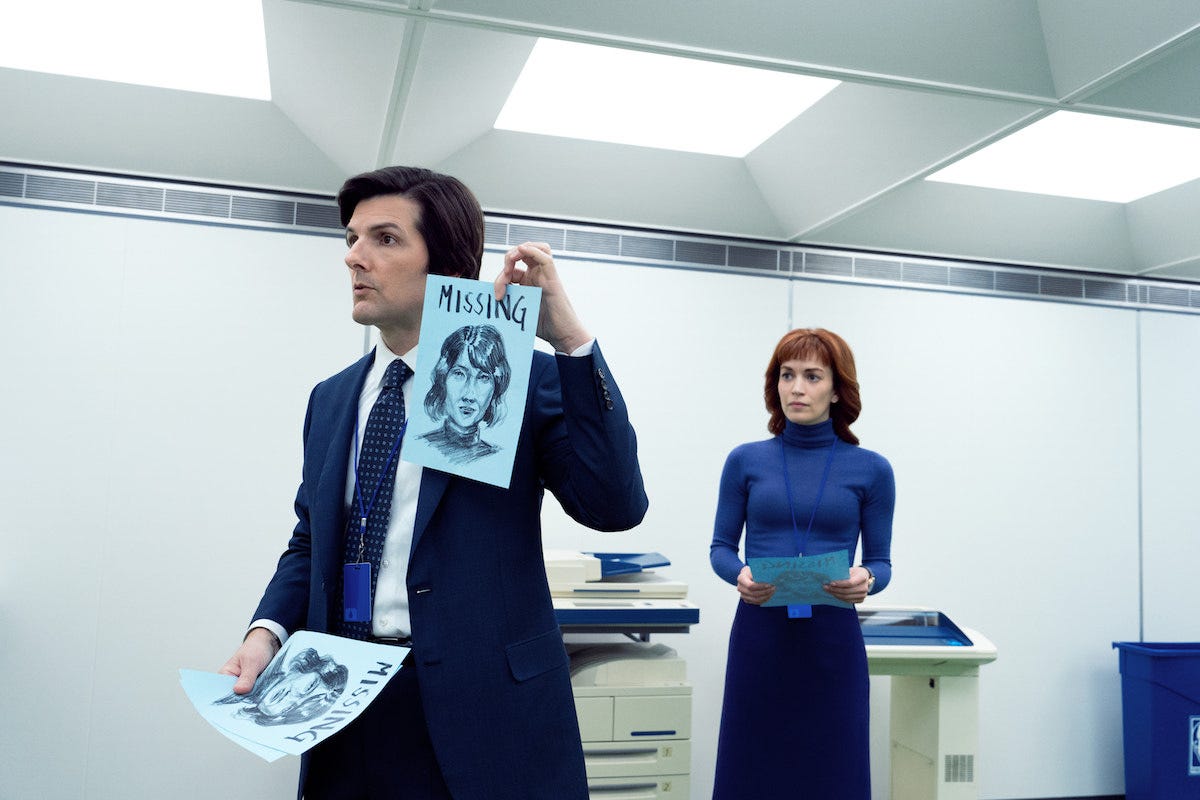

Severance (Season 2)

Apple TV+ • Drama • Undoing Lies

Synopsis

The aftermath of a public revelation spurs duplicity and machination inside and outside the severed floor.

My take

Perhaps fittingly, I’m solidly of two minds about this second season of what I once called a captivating new series.

No doubt, the mind and creative chair of primary series director Ben Stiller still crafts a unique tone, adjoining cryptic grief to a fanciful retro-futurism, that powerfully intrigues audiences, especially those who can and do empathize with the fundamental humanity in that tone but still revel in having to find it within the puzzle box of a setting and a narrative style that prefer to obfuscate rather than ever just reveal their own gestative underbelly. Aided by cinematography that, beyond being simply pretty and clean, literally severs and recedes the series’ “innies” into as miniature a set of figures as they narratively have to be (in the power dynamics of their world), Stiller’s vision of Severance is the promise I described in my take on the premiere season and remains the beating heart of interest in the show that has kept me eager to come back throughout its three-year hiatus.

However, then there’s the way that this second season unfolded. Without saying too much here hopefully — though I do flag potential {spoilers} — I call out the season’s just syrupy languor, stretching without translucency increasingly infinitesimal moments in the lives of its characters without simultaneously maintaining, if not also increasing, the flavor and value of those stretches as elements of the overall meal. Did we need a whole glacially paced 45-min. backstory so late in the season as the eighth episode to learn that Patricia Arquette’s character’s motives are due to her senses of ownership and betrayal over her past work and personal marginalization both at home and at work at Lumon? Why wasn’t this background dropped so much earlier in the season, perhaps even right after we saw her skid away into the night in her car in episode one; and how did learning it do anything but prolong and distract from the only plotlines this season we in the audience actually cared about (i.e., Mark’s reïntegration and consequential “Will they? Won’t they?” quest to recover his distinctly not deceased wife)? Even internally in that episode, the dramatic pay-off of Arquette’s character’s reversal of screw-turning on her domineering and fanatical aunt felt weary, obvious, and underwhelming given the context that came before it; that is, even internally within the episode itself, the dramatic juice felt unworth the squeeze.

So, I worry, readers. I worry that the dramatic and narrative potential baked so well into the series’ premise and first season is being squandered this season (and perhaps also next) on a humdrum fascination with what is ultimately a star-crossed love-triangle (quadrangle?) given expression at the Dan Brown School of Writing. I worry that, like Lost (Lieber, Abrams, & Lindelof [creators], 2004-2010) so notoriously became, the mysterious and nearly supernatural forces at work in the elementary composition and physics of this world are gradually being revealed to be accidentally fascinating gimmickry built without synthetic integration into a larger worldview or tapestry of storytelling to doubtlessly earn the gloss of “impressive,” “memorable,” and “landmark” many are already buffing the series’ reputation by applying. And I worry that continued investment into the characters and the series as a whole, due to these potentially decremental properties of its constitution, will inevitably end in even more profound disappointment for us who’d hoped for and admired the scale and style of its original vision with sincerity and applause from day one.

Did this second season become the nearly monocultural chatter that we should expect to see garner recognition come television’s awards season this fall and winter? Absolutely. Few dramatic series stand up still in merit or value against Severance as a leading contender for what our culture will write down as the “best” dramatic series of the year. (Truly, at the moment, only perhaps The White Lotus [see my take on its third season above], the new series The Pitt [see my take on its premiere season below], and The Last of Us [depending on its Emmy categorization this year; see my take on the second season above] feature in the landscape as potent contenders with Severance for that honorific title.) However, will Severance this season have earned that title, if it win it — or even frankly, if it even just get nominated for it — on the basis of its actual consistent and undeniable quality; or will the mere memory of its peak moments this season, plus the wave of affection its increased reputation over the three years during which its first season went from niche celebrity to wide acclaim, suffice and overwhelm voters’ minds to elevate the entire work to that lofty level? I leave the question now to you, readers, who I know are more than capable of deciding for yourselves.

Temperature check

Tepid

Mid-Century Modern (Series Premiere)

Disney+ • Comedy • Old Unfurls

Synopsis

A wealthy fifty-something gay man invites his two single best friends to live with him and his irascible mother in their expansive Palm Springs home.

My take

Stale air lingers and collects around this nearly carbon copy of Susan Harris’ (creator; 1985-1992) The Golden Girls. Even down to the swinging door dividing kitchen on the right from living room on the left, Mid-Century Modern thinks it can not only survive but moreover thrive on the same old tricks and trades its once groundbreaking predecessor patterned from the comedia dell’arte into the American zeitgeist forty years ago, but ultimately presents less like the charm of a classic reörchestrated for a modern audience than the horrifying if piteous specter of Baby Jane, the anachronistic and delusional fright that birthed ‘hagsploitation’ in the 1960s and consequently a key element of “Queer Codes 101” I’d have wagered any amount that this new series would inevitably refer to during its hopefully either limited or at least eventually vastly improved run. Comedy has just moved on, readers, and, even if I might not be a major fan of everything Hacks is doing this season (see my take on the current season above), at least that series is trying to actually bite the way The Golden Girls actually bit during its original run. This series, on the other hand, settles instead for the dilapidated gumming of an antiquated bone: the stereotypical pacing, the superficial writing, the self-evident choices to seem “heartwarming,” and the niggling tendency to hyper-explain (or is it “exploit”?) in a vainly cosmopolitan fashion the most basic facts about specifically male homosexuality or gay culture as punchlines for quaint “middle American” audiences… The whole production feels just as if an alternative past, in which queerness was still a minority but never a taboo, time-capsuled a sitcom meant for the once idealistically domestic and heterosexual adult mainstream of the 1980s and sent it forward, unedited, into the present day. What are we supposed to do with this antenna TV equivalent? We have 4K streaming now on our phones.

At least if the series were well acted, I could find and hold onto some sincerely funny moments along the way; although the bread may be stale, people still do eat croutons. However, unfortunately for elsewhere brilliant performers Nathan Lane and Linda Lavin, the ensemble has little to no chemistry and the line readings, timings, and energy levels burn and bury any potential for good comedy. I partially blame the casting: Not only does it feel inauthentic bordering on implausible to me that a tight gay friends’ circle has for over twenty years included a 69-year-old Nathan Lane and a 47-year-old Matt Bohmer, but also — and more importantly — who in their right mind thought Matt Bohmer was the best actor for this job? The man has absolutely none of the immense wit of Betty White and seemingly only the talents enough to pull off his shirt to applause.

I pray and wait for this cultural zombie to return to its resting place in history.

Temperature check

Cold

The Pitt (Series Premiere)

Max • Drama • Code Blue

Synopsis

A latently traumatized emergency room physician winces under the strain of managing a perpetually constrained medical workforce, whose members’ motley personalities all bleed into their work.

My take

Perhaps it’s the dissolution (but not extinction) of the once monocultural Grey’s Anatomy (Rhimes [creator], 2005-present), itself the monocultural replacement of the 1990s’ ER (Crichton [creator], 1994-2009), itself the monocultural replacement of the 1980s’ St. Elsewhere (Brand & Falsey [creators], 1982-1988)… but the air did smell conspicuously low of high-profile, high-stakes medical drama lately. So color me largely unsurprised that, like a mushroom in the grass after a rainstorm, another has sprung up in our televisual landscape in the wake of our (now safely distant?) global pandemic.

Frankly, I started watching The Pitt with the near certainty that I’d have the thrill of unceremoniously plucking it and then tossing it away with the other tripe that factory television has tried to serve us of late (e.g., weak procedurals, soapy sitcoms, uninspired drama); but, to my utter surprise as I approached and watched it, I became fascinated by The Pitt’s unique qualities, dissimilar from the nearly entirely watery quality of its most recent predecessor and somehow refreshing in a televisual genre that’s had at least one banner series running every year since 1951 (i.e., the year that City Hospital [Selden (producer)] premiered on ABC). For The Pitt commits itself, unlike its precursor relatives, more to the actual practice of medicine among an ensemble cast than to the ensemble cast itself, yet still manages to avoid the result of that commitment feeling like the clinical, non-narrative gobbledygook of a quasi-workplace drama where the work takes center stage. With that kind of focus, I almost wonder at how series creator R. Scott Gemmill made it through the pitch sessions: Who’d ever want to watch, say, The Office (Daniels [dev.], 2005-2013) if 90% of the action on screen were the actual buying and selling of paper or, alternatively, Succession (Armstrong [creator], 2018-2023) if 90% of its action were the day-to-day management and operation of RoyCo. and its many subsidiary companies? I mean, the compelling if sardonic angle on Succession’s final season was the fact that the coveted and finally vacant chief leadership role of RoyCo. was so desirable precisely *not because* it actually meant or merited any sincere attempt at driving business, but rather because it really meant only the whip hand and pursestrings to govern the rest of the central cabal of festering and mercenary peers. So, really, as unsurprised as I was to see The Pitt début, I was equally surprised to discover its own atypical recipe for success.

And perhaps much of this success can be attributed to the captainship of Noah Wyle, who essentially comes out of retirement from his own ER days to lead this new ensemble in the role of medical chief of staff at the Pittsburgh-based teaching hospital, where the character and his team run a constantly packed but underfunded emergency center as The Pitt’s nearly exclusive setting. In this role, Wyle appears not only capable of, but moreover completely at home with the medical exigencies the story requires, the actor showing off the years of medical training he almost actually has after years on that other mainstream emergency medicine drama. Nowhere is this facility more apparent than in his careful layering between all the diagnoses, exams, and triage an authentic feeling of wherewithal, economy, invention, and aplomb, which any similarly exercised real physician would undoubtedly exhibit in the same situation. While — yes — rote in terms of shape, form, expectations, and execution, this performance is still one of the best from a leading actor in a drama series this year, and I hope it will be recognized as such, with a nomination come the Emmy announcement this summer.

However, I’d be remiss if I didn’t explicitly shout out this new series’ writers, whose work ultimately is responsible for the interest I so surprisingly found in this little but powerful new series. Devising both an interesting and internally dynamic group of characters (from the pushy ingenue to the wizened professional) and an interesting and internally dynamic storyline to send all those characters through, lead series writers Gemmill, Joe Sachs, Simran Baidwan, and Wyle himself, with the support of their fellow writing staff, have crafted a drama that attracts and retains an avid viewership even among those who do not and have never considered themselves avowed to the surfeit of medical fiction unfailingly on television today. While I don’t see or encourage you to expect miracles from this new series, I do see and encourage you to check out one very solid and entertaining new drama.

Temperature check

Hot.

The Studio (Series Premiere)

Apple TV+ • Comedy • Epic

Synopsis

A pinnacularly awkward and anxious supplicant, through a concert of others’ power plays, finds himself at the helm of a major film production studio and, consequently, in receipt of all the never-ending requests and obligations that seat must own.

My take

The most impressive quality of Seth Rogen’s new project, a collaboration with his most culture-critical co-writer Evan Goldberg, is not the writing nor the acting nor the directing but instead the new series’ pure and unrelenting commitment to the peculiar brand of excruciating “comedy” that exacts gripe more than laughs from its audience by repeatedly turning the screws, killing all the darlings, and just compounding social transgressions one on top of the other. It’s the same brand that found its affectionate audience in Curb Your Enthusiasm (David [creator], 1999-2011, 2017, 2020, 2021, 2024) and Veep (Iannucci [creator], 2012-2019), but here that brand is taken to its next logical iteration: The comedic comeuppance socially transgressive characters are supposed to face is here regularly disarmed and discarded with finishes of compassion, compassion that overrides even the small singular zinger the series still inserts right before a quick cut to credits each episode. The result of this “advancement” is that the audience is left with an ambivalent residue of irresolution, or at least diminished resolution, of a kind that forestalls complete catharsis from the stringent dramatic tension the compounding interpersonal blunders enforce and reïnforce. In other words, it becomes Brechtian tenterhooks and, while I personally don’t enjoy the feeling, I have to admit, for this quality — and perhaps this quality alone — The Studio is thrilling.

However, I urge you, readers, look elsewhere if you want lighthearted comedy, free from hand-wringing or vicarious cringe. For a far more straightforward satire of the film production industry, watch Jon Brown’s recent The Franchise (2024; see my original take here) instead.

Temperature check

Tepid

The Handmaid’s Tale (Final Season)

Hulu / Disney+ • Drama • Like a Rolling Stone

Synopsis

Once powerless, the scarred but regrouped former handmaid June Osborne rallies her troops for one final show-down against the hegemonic, proselytic, misogynistic, self-indulgent, hypocritical, arrogant, and ultimately monstrous orthodoxy that stole her family and her freedom from under her feet during its sweeping and nominally theocratic revolution of what was the United States in the early 21st century.

My take

At the beginning of this, the deliberately final season of a dramatic series that was once Hollywood’s television darling (i.e., a series that captured the public attention and imagination and won eight Emmys for its début season), I had hope — not hope for the “epic showdown” the season’s actual trajectory mounted in flimsy belief that it would once again inspire its formerly avid audience (e.g., by finally promising to vanquish the “big bad”) but, instead:

hope that the series had really taken stock of its history and would allow its now heavily battered central characters to find paths toward growth and maturity that would exceed the now palpably provincial parameters under which this series (by its source material) was originally set,

hope that when I did finish watching the season I’d feel as pleased and satisfied with the denouement to this macabre post-apocalyptic fable as I had been with the summarily excellent final season to Sherman-Palladino’s (2017-2023) The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel or Ball’s (2001-2005) Six Feet Under, and

hope that each episode would intentionally and clearly diverge from “what once was” and find and live in the glimmer in “what could be,” *not* because I vainly watch for only optimistic reasons but rather because, after five bullying seasons of repeated if not actually recycled physical and psychological combat against the overarching systems and their flunkies that would keep an adult in chains (actual and metaphorical), who really wants or needs to witness it all a sixth time?

I mean, we get it; the violence, the misogyny, the homophobia, the control, the abuse, the murder… are all terrible, but terrible to the point that continually reëmphasizing how terrible they are in this dramatic context starts to lose its meaning. Similarly, the fight, the opposition, the nobility, the struggle, the small victories… are all powerful and rewarding, but powerful and rewarding to the point that continually rëemphasizing how powerful and rewarding they are in this dramatic context also loses the intended meaning. Is there nothing else that this series can show us or help us to see? Where is the development? Where are the new choices? Where is the point?

Unfortunately, readers, this sixth and final season of The Handmaid’s Tale has no answers to those hopeful and potential-recognizing questions. June Obsorne, despite a single premiere episode that gives Elisabeth Moss the beginnings of a meaty plot-line about moving forward, beyond the tragedy and the betrayals and the vengeance — a plot-line into which, to her credit, she sinks her teeth admirably — nevertheless falls into her old patterns of defying authority, seeking personal redemption through vengeance, and surreptitiously coördinating an uprising to injure if not excoriate the unambiguously evil opposition. Really, were it not for my now years’ long investment into the series-long emotional arcs of some of the characters (mostly because of their actors’ skillful performances), I’m not sure I’d even bother to fully stomach this sixth rehash of “underdog good takes a bite out of domineering evil” that could belong just as well to any season past. For all the vision and portent that the series once had, now it seems, The Handmaid’s Tale already said all it ever had to say years ago. So, all those of you, readers, who abandoned the series one if not two or even three seasons ago appear to have made the correct decision.

Still, thanks to Moss, Ann Dowd, and the rest of the cast and crew of The Handmaid’s Tale for having brought vividly to life for at least one season eight years ago the brilliant terror of Margaret Atwood’s (1985) cautionary ward against oligarchic and fundamentalistic dystopia. We’ll try to remember you as you were then more than as you have been ever since, for while the importance of your first and apparently only message remains undimmed in our culture the living legacy you’ve created for yourself in that message’s afterglow, especially here in this final chapter, bears little to no new light on our on-going condition.

Temperature check

Cold

And Just Like That… (Season 3 Premiere)

Max • Comedy • Tottering about

Synopsis

Wealthy fifty-something New York City women who are unwilling to actually advocate for themselves nevertheless feel continuously suspicious of and disappointed by others who don’t know exactly how to please them.

My take

It’s amazing to me, readers, that a hobbled old shell of a once transformative television series can continue on, into a third season(!), on nostalgia and legacy alone despite its obviously ailing state. How is it possible that, after eight televised and nineteen untelevised but still implied years of experience with life, love, and sex in New York City, this series’ central characters still haven’t learned and matured past level-one problems? Are we really expected to believe that successful professionals (including a literal advocate, a sales expert, and a writer) with that much experience can’t open their mouths or find the words to tell others what they want and advocate for themselves? Moreover, how is it permissible, no less plausible, for these same women to accept and furthermore expect(!) apologies from others who, through no faults of their own except perhaps sincerity and conviction, exhibit the confidence of character to confront unhandsome truths aloud for the sake of acknowledging, managing, and ultimately moving past them? Frankly, I’m sure that, if the same (mostly) commendably audacious women from their original television run were to ever meet these present husks pretending at being their future selves, they’d be appalled and offended by the comparisons.

Can’t we all on behalf of our culture just agree to let this fictional world pass on into memory with whatever honest dignity it may still have? Or are we doomed to keep rëanimating the spiritless corpse of what was once our “it girl” in a vainglorious attempt to proclaim for all those similarly once dynamic and energized but now hopelessly humdrum and homebound American adults, “We’ve still got ‘it’!”? I plea once again (see my take on the series’ second season here) for all of our sakes, readers, that we find the courage to choose the former before inertia commits us interminably to the latter.

Temperature check

Cold (brrr)

Bridget Jones: Mad about the Boy (2025)

Peacock • Romance • Is it too late?

Synopsis

A socially awkward widow romances both a twenty-something valiant and a forty-something guardian in an attempt to digest, understand, and recover from her own personal issues.

My take

You know, readers, for all its deliberately “feel good” qualities, Maguire (dir.), Fielding, Davies, and Curtis’ (wri.) original (2001) Bridget Jones’ Diary did have an authentic edge to its quirky and unapologetically anti-heroic divulgence of modern single womanhood — particularly, for a world only half-way through the original run of Darren Star’s (creator, 1999-2004) Sex and the City. Bridget was relatable, far more relatable than any of those Sex and the City women had been, for the broad audience the studio undoubtedly wanted to capture with as many ticket sales as Fielding’s original novel of the same title had enjoyed as book sales; but, more importantly than being merely relatable, Bridget was also clever, consequently not just catching the attention of but moreover actually earning the respect of those many movie-ticket buyers. And, to anyone paying attention, this pedigree should have come as no surprise.

Bridget the character was deliberately born to update a story that had already stood the test of time by capturing and recapturing an audience’s attention generation after generation through its protagonist’s attractive mix of relatability and cleverness: Jane Austen’s now classic (1813) Pride and Prejudice; Fielding’s Diary was just one way of retelling that classic locally, within a time, place, and vernacular commonly available to, if not actually lived in by, the audience whom it was ultimately meant to reach. Intimate, personal, and very “by the way” in its one, the work was based on and ready for a new era in social manners, courtship, and careerism, one predicated on (for better or worse) computers and their often creative shorthands — a fact that is making me recognize, while literally typing this take out, that it’s precisely the loss of that intuitive and ready connection with contemporary mores, habits, expectations, and modes of communication that keeps this fourth installment into the (now we should expect interminably to be revisited) character and world of Bridget Jones so distinctly out of touch and consequently edgelessly frivolous, especially compared with its original (2001) material. Yes, all the characters and their actors have clearly aged in those intervening 24 years since that original release, in a way that often does in reality fall out of step with advances in technology over the same period; but none of that aging, even if falling out of step with technology, should inherently be a disqualification of the material from meeting if not exceeding the sharp, offbeat, and honestly interesting bar the first film set for us in its audience. While certainly not masterpieces by any stretch, comparable films like It’s Complicated (Meyers, 2009) and Enough Said (Holofcener, 2013) are evidence that it’s at least possible to deliver competent cinematic storytelling about intimate and romantic relationships between people in their 50s and do so notably while using, if not outright relying on, current technology (e.g., FaceTime) relatably and cleverly as a vehicle for the plot. And, honestly, readers, by how few examples of that particular kind of cinematic storytelling I was able to remember, there seems to be a huge opportunity for a new film to enter the culture and genuinely define that subgenre with excellence.

So, my point here is, I would love to see the fifth installment in the ‘Bridget Jones’ film series — or any similarly constructed new film in that subgenre — return to that blissfully contextualized, honestly imperfect storytelling that was substantial enough to earn Zellweger her very first Best Actress Oscar nomination, so that we can for once celebrate rather than deride yet another film whose patent superficial purpose is to placate, if not anesthetize, its “feel good”-seeking audience.

Temperature check

Cold

Nonnas (2025)

Netflix • Comedy • Food for the Heart

Synopsis

A NYC Metro mechanic pays tribute to his mother’s (and grandmother’s) legacy by investing her bequest into a concept restaurant, wherein eclectic nonnas are the chefs de cuisine.

My take

Vince Vaughn’s greatest asset in Hollywood has always been his charisma. From his deliberately endearing films about kinship and/or romance, like The Internship (Levy [dir.], Vaughn, & Stern [wri.], 2014) and Four Christmases (Gordon [dir.], Allen, Wilson, Lucas, & Moore [wri.], 2008), to his otherwise raucous comedies, like Fred Claus (Dobkin [dir.] & Fogelman [wri.], 2007) and Wedding Crashers (Dobkin [dir.], Faber, & Fisher [wri.], 2005), the actor, occasional writer, and producer is most remarkable for projects like this one: comedies with heart wherein Vaughn can provide the amiable lubrication the story’s otherwise entropic machinery needs in order to run smoothly. Ultimately, it’s this quality that cleanly separates all of his films from, say, The Hangover (Phillips [dir.], Lucas, & Moore, 2009) or Jackass: The Movie (Tremaine, 2002), films wherein chaos reigns unchecked and untempered (and perhaps, from their perspectives, even unbothered) by (such nuisances as) sentimental conjunctions.

Now, much in the same way as Jon Favreau worked on Chef (Favreau, 2014) or even Adam Sandler on Spanglish (Brooks, 2004), Vaughn brings his natively comedic charms to work on a relatively dramatic film about a hopeful restauranteur. A likely and perhaps even predictable choice for the actor, since the home and hearth are exactly those warming “ties that bind” that have become at least in mood the actor’s own signature, this new film trades in the pastoral virtues of family, tradition, and cooking that today’s conservative politicians often love to wax poetically about in galvanizing waves of reminiscent nostalgia — a fact about contemporary politics I purposefully interject here in service of the consistently conservative bent of Staten Island, where the film’s feature restaurant is specifically located. While to unfamiliar eyes these pastoral themes may appear the covertly anesthetic woos of any mass market film bottled for opiation, to those familiar with the New York City enclave the same themes are actually just the palpable strands of authenticity, tying the story and its characters firmly to the real people and places on which they are based:

people who ruminate on the always irretrievable past when benevolent grandmothers reliably stirred pots of Sunday sauce to unite a family idyllically undistracted by contemporary ills like social media and technology, and

places that reïnforce the benefits of local proximity and interconnection as sufficient criteria for community and sufficient demand for loyalty.

Therefore ultimately quite different then from Chef or Spanglish, whose own idylls fancy the open road and the necessarily unfamiliar respectively, as well as from Lasse Hallström (dir.) and Steven Knight’s (wri., 2014) more successful The Hundred-Foot Journey and Trần Anh Hùng’s celebrated (2023) The Taste of Things, two other films that also focus on the life and memory of beloved female chefs and matrilineal culinary traditions but romance less the conviviality of an abundant meal than the dedication to and the appreciation of an exploratory and inventive mindset (i.e., one that can connect the traditions of the past with the opportunities of the present for the benefit of the future), Nonnas despite a veneer designed to erase any trace of political commentary from its runtime in order to appear just an authentically grounded and generically heartwarming story about food and family (biological or chosen) nevertheless turns out to be one of the most deliberately political statements via food and food-making cinema I can think of in the history of film — well, definitely at least since Brad Bird’s nearly diametrically opposed (2007) Ratatouille. Hinging on a perspective best described as “low openness” à la the “Big Five” factor model of personality traits, the film gently appeases only a worldview that cherishes what’s past, what’s familiar, and what’s local at the necessary expense of what’s new, what’s different, and what’s worldly. While perhaps authentic to its real inspiration and superficially innocuous enough to avoid tripping the alarms of most snacking viewers, the message nevertheless present in big macaroni letters for anyone conscious enough to step back to view it remains: Cleave to and fight for the familiar greatness you once knew. Sound familiar, anyone?

While I never expected to write politics here, especially for an “obviously” feel-good film about food, I can’t avoid the palpable themes and their necessary implications in this new release. Whether you be for or against those undergirding arguments, I at least recommend you digest this dish with an awareness of what your’e eating and, if you happen to hold a different worldview, ask yourself whether you can truly ever enjoy, however warm the meal, the handiwork of a contrapuntal ideologue.

Temperature check

Tepid (barely)

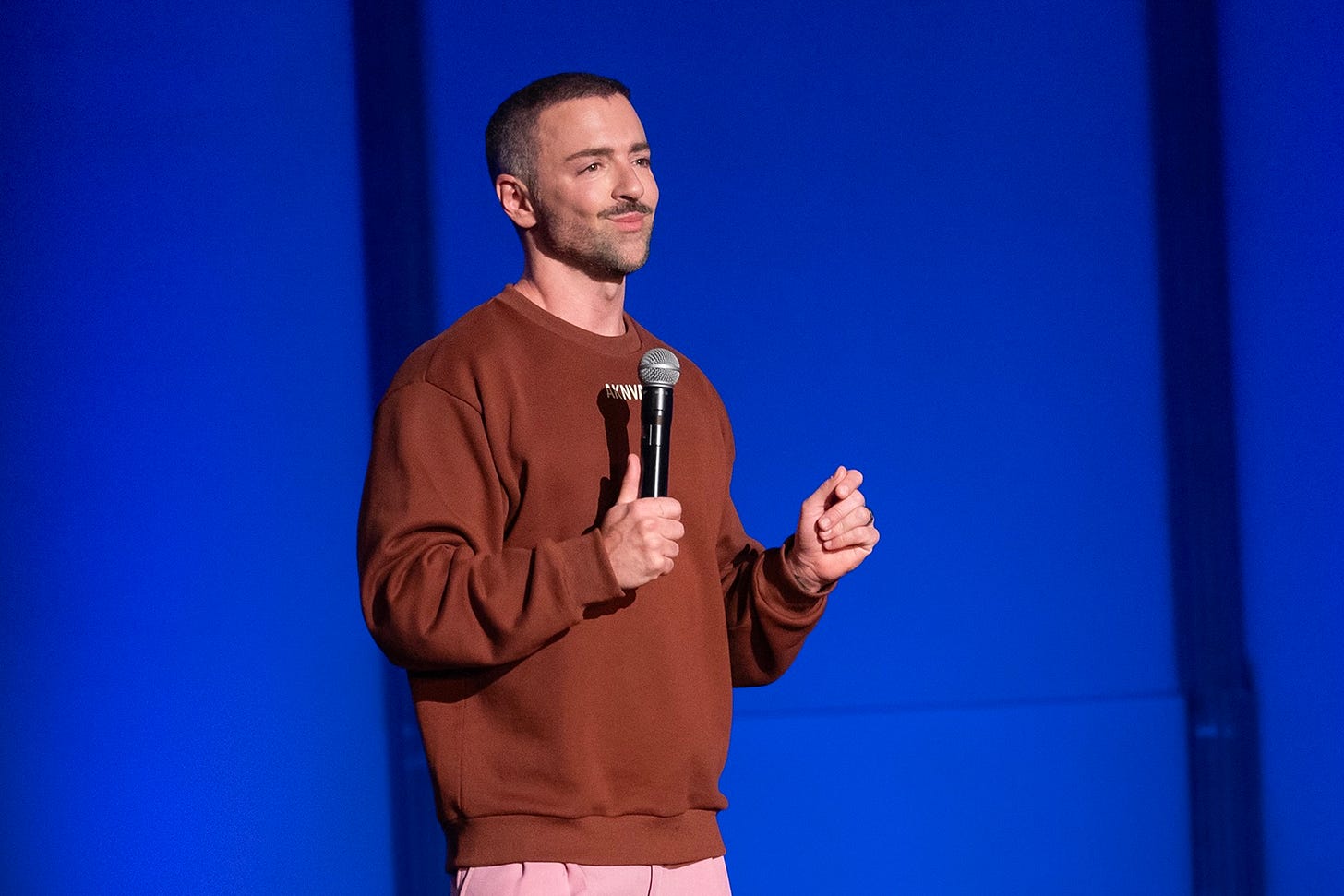

Matteo Lane: The Al Dente Special (2025)

Disney+ / Hulu • Comedy • Chatter / Folderol

Synopsis

The quarter-Italian, quarter-Mexican, and half-Irish American comedian swans through droll excerpts from his life at home, abroad, and at pop music concerts.

My take

As fun as it may be for fans of the “obviously gay” NYC-based comedian to see him perform on the big medium screen in a dedicated special, Matteo Lane, unlike say Jerrod Carmichael in his Emmy-winning special Jerrod Carmichael: Rothaniel (2022; see my original take here), does little to differentiate this event from the casual and familiar tropes and jokes of his greater social media presence. While this redundancy to a certain extent may be acceptable and even expected for a relatively niche performer playing for the first time on a broader stage or platform whereby completely unfamiliar audiences may first encounter and experience the performer’s particular style and show, here Lane’s deliberately impersonal style, favoring broadly recognizable identity caricatures over an authentic and unique perspective in service of humorous storytelling, colors at least the better part of the show with a perceptible sense of interchangeability that resists rather than invites the audience into Lane’s declaratively lived experience(s): While Lane’s vocal intonations do dress up the comedy in those segments with a mild but definite original flavor, the content and impact of the stories and their jokes in those segments could be almost anyone’s — an unfortunate unremarkability that defies relatability on a direct path to anonymity and, consequently, forgettability. It’s not that the experience during all those unremarkable-to-forgettable moments wasn’t entertaining while being experienced; it’s far more that I’m certain I wouldn’t be able to uniquely recall or place any of those moments in my memory as belonging to this special and not any other. After all, “who is speaking anyway?” is not the question one wants to be asking while actively watching a stand-up special.

Now, clearly, to the extent that this voicelessness is offenselessness, the special will no doubt beget a certain clapping complaisancy from the mass audience that consumes it and Lane will no doubt gain new fans from the exposure. However, all those extant fans he might already have and anyone else not satisfied with the “one size fits all” take on comedy Lane deliberately tries to sell here — a product that, even in a sociocultural climate less partial to the highly individualized and deliberately vulnerable packages of a comedy than the one in which we’ve been living now for the past decade (if not more; recall, beyond Carmichael’s Rothaniel, Hannah Gadsby’s Emmy- and Peabody-winning work on Nanette [2018] and Bo Burhnam’s Emmy-, Peabody-, and Grammy-winning work on Inside [2021] for examples), would be a challenging sell — will find themselves lamenting the opportunity cost of being served such an anonymous meal instead of receiving an expanded version of those few brief passages that actually reveal Lane’s distinct and admirable perspective, which really is the asset that has earned him his relatively large social media following. For the sake of that real potential in the comedian, I hope that those few passages are enough for those newly acquainted viewers to dig in more; but, I have to say, my confidence with that hope’s manifestation is low.

Temperature check

Cold

Black Mirror (Season 7)

Netflix • Sci-Fi • Remember Me

Synopsis

Six new episodes focus on the double-edge sword technology can be in life, love, and loss.

My take

It’s no secret that my temperature on Charlie Brooker’s once thrilling Black Mirror has been cooling over the anthology series’ past few seasons (see my take on season six here); where the series once excelled at imagining technological futures in which humanity is hoisted for better or worse on its own petard, the series more recently has languished, content with elaborate but precarious balances of perverse technical constraints and dramatic human choices. While such concocted dynamics are descriptive of the recipes of even the series’ most successful episodes (e.g., “Nosedive,” “White Christmas”), they alone cannot a successful episode make; instead, plausible future technologies creating contexts for incisive philosophical debates about relatable ethics in conflict with personal or human interests in those technologies’ applications better account for the complex chemistry that once made the series so popular and outstanding — a fact that Brooker’s nearly solo writing for the series has seemingly yet to fully comprehend.

And, while this seventh season overall does a better job at replicating that complex chemistry than the few seasons before it, little new ground is ultimately explored by Brooker’s experiments beyond where we’ve seen the series go before. To wit, for the first time a true, within-universe sequel episode appears in the anthology, revisiting and rehashing the same ethical debate (about ownership vs. individual autonomy in a world running on AI technology) via the same characters and setting as the original episode (“U.S.S. Callister”). Even the season’s newest plots, the two episodes that held closest to the through-line of the series, “Common People” (episode 1) and “Hotel Reverie” (episode 3), feel less like net-new additions to the Black Mirror canon than gross-new twists on existing material.

“Common People” is — spoiler alert — a blend of:

Season 1’s “The Entire History of You” (in which cerebral implants compromise the health of a romantic relationship) and

Season 3’s “San Junipero” (in which romantic partners learn how to say ‘goodbye’ to one another) while

“Hotel Reverie” is a blend of:

Season 4’s “Hang the DJ” (in which a virtual environment gives two people the chance to explore what a romantic relationship would look like),

Season 3’s “Playtest” (in which visiting a simulated environment risks being trapped there forever), and

again “San Junipero” (in which romantic connections are made between people of vastly different ages).

Perhaps it’s time then, or has been time now for a few seasons, to let other writers take the wheel of this series — if only to let other voices, with idea banks unentangled from the fundamental ideas that have grounded and shaped the series to this point, tell us stories that would still fit well underneath the Black Mirror banner. For it’s not a lack of interest, that has let my feelings cool on this series otherwise; it’s actually a surfeit of interest in specifically high-quality storytelling, that makes me want more for this series that has occasionally brought us some of the best contemporary sci-fi writing on television.

Temperature check

Cold

Dying for Sex (Series Premiere)

Disney+ / Hulu • Comedy • Give and Take

Synopsis

The metastatic return of her breast cancer prompts a forty-something New Yorker to upend her life in search of physical and emotional fulfillment.

My take

By far the best actor ever to grace what was once “the WB,” Emmy winner, Oscar nominee, and surprising Grammy non-nominee Michelle Williams has once again chosen savvily for herself: a real-life-based character split into nearly diametrically opposite flavors, one a medical tragedy rife with the potential for drama and the other a sex comedy rife with the potential for humor. It’s the superficial conflict between the two that is the tension and challenge her character has to face in this new series, and it’s the portrayal of that challenge that affords her the unique opportunity to demonstrate her range in an entirely new way, one fundamentally distinct from her last roles on television and substantial (and sympathetic) enough to remain competitive for further awards come year end. All she needs to do is execute.

And execute she does; Williams’ capable and harmonically varied performance is strong — albeit definitely not the strongest she’s ever given (see her stunning work in Fosse/Verdon [Levenson & Kail (dev.), 2018] for that honor).

However, my words here, rather than expand on the virtues of another good Michelle Williams’ performance, I think are better spent on discussing the writing for the series. While it’s obvious from the show’s premise why this series was greenlit in the first place — that is, why *apart* from its real-world basis, which inherently makes any such “powerful” story more appealing to the viewing public — what’s not obvious from that premise alone is that the series fundamentally uses the spectre of death as a permission card for diving headfirst into the deep and socially “dangerous” (or at least murky) waters of sex and sex discourse. This contrivance bothers me. Why, in the year of our Lorde 2025, does a new television series on streaming television need this mechanical and dialectic ‘excuse’ to confront sexual topics in a narrative format with seriousness, comedy, or just frankness? Hasn’t the whole of “middle America,” or whoever the people most likely to clutch their pearls over the ‘taboo-breaking’ content an unabashed sexual exploration promises are these days, been reared by now on the sexual (mis)adventures of the characters on Sex and the City (Star [creator], 1998-2004)? I mean, isn’t that why so many hordes of tourists from elsewhere in the country make what in their minds are sacred pilgrimages to NYC, specifically to the steps where the iconic series was often filmed, to have their photos taken and perturb the homeowners of the real private residence there to the extent that those homeowners have now erected a gate to literally bar those pilgrims from their unwelcome trespassing? What possibly does a story about the newly promiscuous life of a heretofore sexually mild middle-aged woman have to add, that this culture hasn’t already seen and heard, if not several times over by now, then at fewest once across various popular and unpopular series and films, including:

Sex / Life (Rukeyser [creator], 2021-2023),

Sex Education (Nunn [creator], 2019-2023),

Hung (Burson & Lipkin [creators], 2009-2011),

Big Love (Olsen & Scheffer [creators], 2006-2011),

The L Word (Chaiken, Abbott, & Greenberg [creators], 2004-2009),

Masters of Sex (Ashford [dev.], 2013-2016),

Industry (Down & Kay [creators], 2020-2024),

Queer as Folk (Cowen & Lipman [dev.], 2001-2005),

Sens8 (Wachowski, Wachowski, & Straczynski [creators], 2015-2018),

Skins (Elsley & Brittain [creators], 2007-2013),

The Golden Girls (Harris [creator], 1985-1991),

Fleabag (Waller-Bridge, 2016-2019),

Euphoria (Levinson [creator], 2019-present),

A Teacher (Fidell [creator], 2020),

The Great (McNamara [creator], 2020-2023),

Spartacus (deKnight & Raimi [creators], 2010-2013),

Unfaithful (Lyne [dir.], Sargent, & Broyles [wri.], 2002),

Fifty Shades of Grey (Taylor-Johnson [dir.] & Marcel [wri.], 2015),

Secretary (Shainberg [dir.] & Wilson [wri.], 2002),

The Crying Game (Gilbert [dir.], Hastings, & Hodges [wri.], 1994),

Last Tango in Paris (Bertolucci [dir.], Arcalli, & Varda [wri.], 1972),

Anora (Baker, 2024),

Shortbus (Mitchell, 2006), and

Cruel Intentions (Kumble, 1999)

?

(And, for the record, I didn’t stop listing examples here because I ran out of them; I stopped because I got tired of listing the so so many there really are.)

The answer (to that last question) is, in my opinion, very little. Stemming off the series’ very close relatives — on one side The Big C (Hunt [creator], 2010-2013) and Wit (Nichols [dir./wri.] & Thompson [wri.], 2001), previously televised explorations of fighting for life (in various expressions) after a diagnosis of cancer, and on the other Sex / Life and Sex and the City — the strongest addition the series makes to the existing discourse is really just the relatively mainstream injection and approval of puppy play, which I can’t recall ever having been taken quite so seriously within a television series until this point. While not nothing, this small component within the greater arc about the sexual liberation of an adult woman is at best a faint achievement unworth much attention from a general audience.

Perhaps if this nominal comedy were more deliberately funny, I’d feel more inspired to call out its qualities over its gaps; but ultimately I can’t defend much other than the series’ acting, which provides a true representation of the on-paper tonal and narrative “mixed bag” the protagonist’s life and choices create.

Temperature check

Cold

Adults (Series Premiere)

Disney+ / Hulu • Comedy • Zoomer Strife

Synopsis

Four twenty-something roommates (plus one significant other) stumble through their first steps outside the safety and familiarity of adolescence and into the novelty and uncertainty of adulthood.

My take

While tonally perfect in recreating the topics, the choices, and the dialogue that real versions of its five central characters would undoubtedly discuss, make, and say, Adults, the kinetic brainchild of two writers for The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon (Fallon & Miles [dev.], 2014 - present), may ultimately be too plausible to achieve its comedic goals. Though each of the central characters is inherently comically inept in one or more domains of making decisions and commitments (e.g., self-advocacy, knowing one’s limits, reading social cues, choosing a profession) and while clever premises provide ample opportunities for those ineptitudes to whirlwind each episode’s plot off its axis (in the way, for example, the best of Seinfeld [David & Seinfeld (creators), 1989-1998] so successfully did), the foolhardy ramps never seem to go far enough to really earn back the credit their audience wants to lend the series in the form of suspended disbelief. Sure, mistaken identities and bizarre gambits lead to obviously contrived and quintessentially comic situations the characters must then painfully navigate while nevertheless strapped by their own unrefined impulses and fears, but — spoiler alert — accidentally going too far at work and consequently losing one’s job aren’t, for example, experientially far enough away from especially the series’ target audience — i.e., similarly green zoomers who’d find the characters’ personalities and living arrangements, if not actual foibles, deeply familiar — to land with laughter the way the writers and cast so clearly want them to. Gen-Z audience members and other viewers may indeed find the specifics of those experiences in the series exaggerated and consequently absurd, but simultaneously all too recognizable and even relatable to laugh at with any sincerity. So, while Adults may pattern itself off the exponentially absurd laughter mechanics that made series like Seinfeld and Frasier (Angell, Casey, & Lee [creators], 1993-2004) massive mainstream hits and may want to live within the variably comic tradition of popular series featuring diverse casts of eccentric but relatable young people “taking on life and all its challenges” (especially Friends [Crane & Kauffman (creators), 1994-2004], Girls [Dunham (creator), 2012-2017], and Workaholics [Anderson et al. (creators), 2011-2017]), the series plays itself too safe to leave a lasting impression — except perhaps a tragic one for all the social (and occasionally physical) pain we the audience have to watch its relatable characters endure in order to hopefully build up the wherewithal to actually become functioning adults in our society.

I laughed twice.

Temperature check

Tepid (just barely)

I’m purposefully omitting Arrested Development’s return seasons in 2013 and 2018-2019 to make this point.

Here I knowingly omit past series like Buffy, the Vampire Slayer (Whedon [creator], 1997-2003) and True Blood (Ball [creator], 2008-2014), which I’d argue are better described as romantic soap operas with a supernatural theme than true horror series per se.