[Hot Tea] My Personal "Top 10" Films of 2022

My thoughts on the best from this past year in film

Readers, after my last post (presenting my takes on this year’s ten ‘Best Picture’ Oscar nominees), many of you sent in messages asking what my personal Top 10 films of 2022 are, or — more precisely — what I would recommend you see instead of those few less exciting options among this year’s Oscar nominees. So, in these last few days before the Oscars, I thought, what better a way to capstone the film year than to fill in that gap, answer those questions, and share some of the films I seriously think the Academy overlooked but you, reader, should not.

Before I dive in, I think that it’s crucial to say what most list-makers don’t take the time to say: what criteria or qualifying merits decide whether a film earn a spot on the list. When other list makers leave these criteria out, I often worry about the integrity of their comments.

For most other self-appointed film ‘gurus’ out there, these lists become simply slates of “favorites,” or “what I happened to personally enjoy most or like best out of the prior year’s offerings” — which, frankly, as the one criterion for a year-end list makes me cringe. How is telling me what you happened to ‘like’ best a good guide for me as a reader to navigate the sea of films released in the past year? Unless you and I share uncommonly personal tastes, diets, or allergies, the food you happen to like eating most is hardly likely to thoroughly delight, let alone nourish, anyone.

For some others, the lists are ways to credit “below the line,” technical achievements in filmmaking that the list-makers hope general audiences do not neglect. “Yes,” they say, “Actress A did give a fantastic performance in Film B, but don’t miss out on Film C, where the art direction is incredible.” As a film aficionado, I can much more readily get behind this type of end-of-year list-making than the prior type, simply because I’m into those technical aspects of film-making; BUT there is a reason I keep my awards’ site, celebrating the skills in all “below” and “above the line” categories, separate from this reviews-focussed site: Most other people don’t really care about the technical achievements in films, especially those films that otherwise failed to come together as narrative (or even occasionally documentary) entertainments. So, technical achievements alone aren’t good enough for me to use as bases on which to recommend any film to you, readers, this or any other year.

For a final few list-makers, perhaps those most deeply immersed in the broad landscape of films released each year, the lists each act as a means to elevate what might otherwise be ignored as “small,” “independent,” and/or “international” films — disappointingly “dirty” words sometimes, when general audiences think about going to the movies. These are films that simply did not have the funding, the commercial potential, or the studio power to raise enough awareness for themselves in order to make it into contention for mainstream Top 10 lists of the prior two kinds. However, for me, again, although this type of list-making makes for generous and charitable grass-roots film marketing and may raise the profile of some smaller indie or foreign films audiences would otherwise not know about, no less see, charity and marketing aren’t really what a Top 10 end-of-year list is supposed to be about (in my opinion).

My list, readers, is therefore really none of the above; while each of those above types of list has its individual merits attached to the viewing interests of the reader, my list, like every post in this Hot Tea series, is about assessing the cultural and cinematic worth of each entry (here, each film released in the prior year) and delivering to you a digest of only those films whose worth is, very simply, the highest. This assessment ideally operates regardless of all the other factors such as personal liking, specific technical achievement, or underdog status. Yes, inescapably, personal liking, an appreciation of technique, and an elevation from the sidelines may each and all enter into how I discuss and comment on the worth of any or every film; but, let it be known clearly, I have a deep respect for some films I personally did not enjoy watching (and frankly hope to never see again), I hesitate to uphold any film that doesn’t come together overall simply because its one or two technical achievements may be world-class {ahem, Avatar: The Way of Water}, and I do not believe that coming from the sidelines is a sufficient qualification for recognition. No, to me, the films that make it onto my Top 10 list here are simply the most worthwhile overall achievements in cinema for anyone who is even only slightly interested in the art and science of film-making and at least passively participating in our larger culture. Only those films with that kind of viewer in mind, I believe, make a good guide for any traveller in our great film landscape.

Now — last proviso — because the Oscars aren’t all bad and streaming release schedules have meant that some 2022 films have already appeared in prior servings of Hot Tea, wherever the films in my Top 10 overlap with takes I’ve already given I’ll mostly refer you, readers, to what I’ve already said by both linking to and reposting those original thoughts. (Don’t worry, avid followers, however; there are certainly new entries here too.)

Without further ado, I present my ‘Top 10 Films of 2022.’

Films are presented in alphabetical order.

Aftersun

Rentable • Drama • Papa, Don’t Preach

Synopsis

A summer holiday in Turkey leaves an eleven-year-old girl with profound questions about her thirty-year-old father.

My take

Paul Mescal rightfully earned himself and film-maker Charlotte Well’s gorgeous Aftersun mainstream recognition this season with his nomination for Best Actor at this year’s Oscar ceremony. If only the Academy had been more aware of the film’s quality in its other branches, we might have seen it take its rightful place among the ten ‘Best Picture’ nominees, as well as the nominees in several other categories (perhaps most notably writing and directing).

Wells, who wrote and directed this autobiographically inspired film about an eleven-year-old girl’s holiday with her thirty-year-old father, poured sensitive and personal yet still relatable truths from her own lived experience into this new story examining the depths and limitations of interpersonal knowledge through the lens of a father-daughter relationship. So capable a grasp does Wells have on telling this superficially simple story, that she serves what to uninitiated eyes (like those of the people who form the backdrop of the main characters’ storylines) seem like unremarkable everyday gestures in simultaneous layers with utterly remarkable memory-worthy departures from those everyday constraints, into the realms of the deep emotion, connection, and dissociative trauma. The visual language she and her crew choose, levelling objective plot points with an abstract realism in light and color, is the true magic of this film; and it’s only a testament to this magic and his acting skills, that Mescal can hang on and channel the vision Wells so clearly has for her output into a materially spectacular performance.

For all the ways J.K. Rowling’s “Wizarding World” series did go wrong as both a work of literature and an entry into our common culture, one solid thing I hold as right within that world is her conceit of the pensieve, a magical instrument in the shape of a bowl, enabling anyone with access to a memory (there, a tangible if diaphonous silvery fluid) to actually relive it, to effectively swim in it. Aftersun is above all things such a memory, beautifully articulated, that we as the audience may find ourselves lucky enough to swim in; and I am grateful to have had that chance this year, via our common culture’s version of a pensieve: the (equally silver) screen.

Aftersun won the ‘Outstanding Début’ awards from the Directors’ Guild of America (DGA), the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA), and the National Board of Review (NBR) and is a six-time nominee this year at Rich Picks, in categories including Actor in a Leading Role, Director, and Live-Action Feature. It is now the official ‘Rich Pick’ in Editing.

Temperature check

Hot

All That Breathes

HBOMax • Documentary • “And the pismire is equally perfect”

Synopsis

Personal, social, and international issues converge on the minds of three businessmen, who on the side care for the black kites native to their New Delhi home.

My take

It’s often a sad truth that excellent documentary film-making gets recognized at the end of each film year only in the specific categories labelled for documentaries. It used to be the case that animated film-making went the same way, although in recent years we’ve seen (especially with the expansion of the Academy’s ‘Best Picture’ line-up from five nominees to ten) animated films reach into other categories including ‘Best Picture.’ When will the same be true for documentaries, I wonder? Other than last year’s absolutely riveting and boundary-breaking Flee (Rasmussen [dir./wri.] & Nawabi [wri.]), nominated in the Animated, Documentary, and International Film categories, and the occasional “Original Song” nomination for a bigger-budget documentary like Melissa Etheridge’s nomination for Gore and Guggenheim’s (2006) An Inconvenient Truth or Lady Gaga and Diane Warren’s for The Hunting Ground (Dick, 2015), documentaries scarcely ever make it beyond recognition on their home turf. I mean, it’s been nearly thirty years since we saw a documentary even break into Editing (see Hoop Dreams; James [dir.] & Marx [dir./wri.], 1994).

Well, even with all that history on my mind, it still seemed possible to me this year, readers, that the new documentary All That Breathes break the pattern, specifically with a nomination for its cinematography. A rapturous (and coincidentally raptor-ous1) meditation on the tension between the natural world (of which, it dutifully reminds us, we humans are still a part) and the world of cities, in which people attempt to scratch out meager existences with some shreds of untrammeled dignity, the film is the best thing to enter into the documentary category this past year by far.

And — I’ll say it again for emphasis — one large part of this film’s excellence is its absolutely gob-smacking cinematography. Readers, I tell you, I seriously had to keep reminding myself that the film was a documentary, because — unlike so many documentaries whose visuals, because of the very nature of documentary film-making, have to be whatever shots happen to contain the real events in focus best — All That Breathes presents the clearest, most patient, most meditative shots (including dynamic panoramas and difficult interiors) I’ve ever seen put together a story of real events. It’s truly documentary cinematography on the order of the Maysles’ in their (1975) Grey Gardens: intelligent, purposeful, and expressive well beyond objective; and it takes all the best notes from other visual artists interested in the frontier between stark nature and rampant humanity (like photographer Nick Brandt), from more “templatized” nature documentary (like David Attenborough’s best on-site work), and from straightforward documentary ‘news’ reporting.

However, there is far more worthy about this film than just its cinematography. Culturally, it is a essentialist’s portrait of changing times, of how the industrialized machinery of a growing metropolis often forgets to acknowledge, let alone leave any room for, the individual components it once needed in order to survive, no less thrive. Kites, people, bonds, habits, habitats, and freedoms all qualify and align as those components, passing through time to their potential obsolescences like any material part, worn down by years of (dis)use and pollution into a solemn shadow of its former self; and yet, through collective action, if groups desire it, maintenance and upkeep crucial to long-term survival can keep important arteries clear and healthy while restorative actions can keep the aptly named ‘all that breathes’ adaptive to the rapidly changing environment. Reminiscent in this way of past documentaries like An Inconvenient Truth (though here far more elegant and descriptive) and like Chris Killip’s (1988) In Flagrante (though here far less committed to the past), All That Breathes is a hopeful if highly uncertain love letter to the natural world we so often forget.

All That Breathes is a nominee for ‘Outstanding Documentary’ (or equivalent) by the Directors’ Guild of America (DGA), the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA), the Producers’ Guild of America (PGA), and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) at the Oscars; a “Top Five” finalist for Best Documentary by the National Board of Review; the winner of the Grand Jury Prize for ‘Best Documentary — World Cinema’ at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival; and a nominee for ‘Best Cinematography’ by the American Society of Cinematographers (ASC). I have nominated it in two categories this year at Rich Picks, and it is now my official pick in both: Documentary Film and Cinematography.

Temperature check

Hot

The Banshees of Inisherin

HBOMax • Drama • Compromise

This entry was originally published in my last post, documenting my takes on this year’s ten ‘Best Picture’ Oscar nominees. It is repasted in its entirety here, with an italic addendum describing the film’s current highest honors.

Synopsis

The sudden and unilateral decision of a musician to terminate his life-long friendship with a farmer unsettles an otherwise quiet seaside community.

My take

Fourteen years after their successful collaboration on the charming In Bruges (2008), writer and director Martin McDonagh (coincidentally also a 2022 Tony nominee for ‘Best Play’ for his darkly comic Hangmen) and actors Colin Farrell and Brendan Gleeson (whom, I’m guessing, many millennials will best remember for his turn as Alastor ‘Mad Eye’ Moody in Yates and Goldenberg’s [2007] Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix) reünite on the dim shores of Ireland for the deeply introspective The Banshees of Inisherin. Almost a chamber piece, set in a small and otherwise quiet seaside village in 1923, the film is a sonnet on the weight and meaning of people and work, or rather people vs. work, in life. At times heartbreaking and at others delightful, the story is one of the most sophisticated printed on film this year and, unlike the prior two films in this list, is strikingly unique in the history of narrative films I know.

Mostly closely related visually and thematically to other pastoral dramas about interpersonal intimacies like Ang Lee and McMurtry and Ossana’s (2005) Brokeback Mountain, Francis Lee’s (2017) God’s Own Country, and Ang Lee and Thompson’s (1995) Sense & Sensibility and yet somehow still nothing like those other films at all in its actual text, Banshees is interested less in the cautious culmination of a bond than in the aftermath of its (here abrupt) dissolution, a subject usually reserved for films about untimely death (e.g., Meet Joe Black; Brest et al., 1998), if truly for any film at all. I mean, I really cannot think of any other example of a film in which a break-up catalyzes the plot and does not — spoiler alert — result in new bond-making for the central characters — and how refreshing it is to see someone for once carefully consider the end of a relationship’s lifecycle not bereft by death without the rose-colored glasses to tell the audience to buck up à la “It’s all going to be OK in the end.” Truly, for such a natural and obvious part of the human experience to go essentially untreated on the screen for so long, it’s almost a miracle we haven’t yet seen such a film already and it is a startling success for McDonagh to have put his finger so squarely on that gap.

Despite this uniqueness in story and the palpable excellence in that story’s execution (featuring texturally rich visuals, a haunting score, and career-best performances from Farrell and supporting actors Keoghan and Condon, who both by the way just won the British Academy’s awards for the year’s best in their respective categories on Sunday), Banshees is likely to end up resembling some of its visual relatives in more than just setting and tone: It’ll likely finish, like Brokeback Mountain and Sense & Sensibility, first runner-up in the ‘Best Picture’ race, each in a loss to a more popular competitor. While, true, it’s fate is yet to be sealed by the official votes of the Academy on that front, the film nevertheless remains one of the year’s strongest as a highly worthwhile addition to our common culture and should thus not be overlooked.

Temperature check

Hot

The Banshees of Inisherin is a ‘Best Picture’ (or equivalent) nominee by the Directors’ Guild of America (DGA), the Producers’ Guild of America (PGA), the Screen Actors’ Guild (SAG), the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA), and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) at the Oscars; a Top 10 film by the National Board of Review (NBR); and the winner of the ‘Best Motion Picture — Musical or Comedy’ Golden Globe by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association (HFPA). I’ve nominated it seven times this year at Rich Picks, in categories including Original Screenplay, Director, and Live-Action Feature; and it is now my official pick in three categories for its fantastic performances: Actor in a Leading Role, Actor in a Supporting Role (specifically, for Barry Keoghan), and Actress in a Supporting Role.

Living

Rentable • Drama • Tick-tock

Synopsis

Upon receiving a limited prognosis, a bureaucrat reëvaluates how he’s spent his time.

My take

This one is a slow burn, readers. If you’re down for this kind of staid British-Japanese drama of manners, then read on.

OK, the first thing I feel obligated to say here, readers, is that, sadly, I am not already familiar with Kurosawa’s original film Ikiru (1952), upon which this newer film is based. So, unfortunately I can’t comment on the quality of the adaptation, its position as an update after seventy years, or its transplantation into British soil.

What I can say, however, is that its current adaptor, Kazuo Ishiguro, 2016 Nobel Laureate for Literature and author of the novels including The Remains of the Day (1989; which later became one of my favorite cinematic adaptations), is probably the perfect person to complete a translation of Ikiru to mid-century London. Ishiguro, now an Oscar nominee for his work on this film, is a Japanese man who grew up in the mid-century U.K. after his parents moved him there at the age of five. His writings betray his fascination with and appreciation of the world of manners and service, one in which (I’m guessing) he was steeped while growing up. The effect of this strong and cross-cultural impression on Ishiguro as a writer is his distinct sensitivity in scrutiny, turning what could otherwise be tense inspections of rules and regulations into the tender criticisms only a loved one or intimate could have, seeing at once both the light and the dark sides of a relatively divisive personal or organizational practice.

In Living, Ishiguro’s skill in creating a world that is deftly at once both a smooth and polished machine and a soul-evaporating wasteland is evident even in the smallest touches. In an early scene, Nighy’s character, Mr. Williams, a middle-management functionary bureaucrat, happens to be in an “upper” hallway, frequented primarily by his esteemed superiors, when one such superior approaches. Despite the width and vast emptiness of the hallway, Williams pulls to the side and remains still there, like any courtier at the sudden presence of the monarch or any self-identifying peon at the presence of known dignitary, out of patience and reverence until the man, who doesn’t even return Williams’ courteous greeting with a glance in his direction, has fully passed by. A simple interaction, fleeting but clearly emblematic of both the ethos of the protagonist whose journey we’re starting to follow and the world in which he’s attained a degree of success in navigating, sets the tone for the entire plot — and it’s just one of many carefully curated aspects of the screenplay (e.g., the tight quarters of the central office, the explicit instruction on the train platform at the very start of the film), to help the audience understand, as Ishiguro and the rest of the filmmaking team understand, the weight and the pace of life in this strange yet familiar and only remotely past world.

The solemnity, deference, and patience bleed through all the other aspects of the film admirably. Nighy strikes a clean harmony with the intent of the piece and charmingly and disarmingly reduces the usually brash timbre of his voice down to a floating whisper, to acoustically represent his part. In costumes, Sandy Powell’s tight, clean lines and thick, saturated colors quietly remind us of the subtle work the environment does to reïnforce these habits into traditions and then expectations for everyone living within them, especially when her alternative loose shirts and brown fabrics (decorating and representing people outside the establishment) provide a contrast.

Ultimately, this quiet gravity, accumulated slowly over time like a potential energy built-up on a passively loaded spring, weighs down the level of the action in the plot so much that the relatively minor departures the characters take from their otherwise prescribed lives feel like extraordinary releases from the emotional, physical, and social strictures to which, in the names of orderliness, politeness, and face, they’ve implicitly agreed to succumb. It’s the magic in these departures, the subtle and simple beauty of communing with the greater paces of life, that gives Living all its best and most memorable passages and, for me at least, emotionally affecting finale.

While the film is definitely not perfect (e.g., Aimee Lou Wood plays an important contrast and catalyst in the film without ay complementary depth to Nighy’s), where Living does manage to succeed and what it does manage to say with that success do certainly place it for me cleanly within the Top 10 films of the year.

Temperature check

Tepid (unless you also like a slow burn)

Living is a nominee for ‘Outstanding British Film’ by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) and is a Top 10 Independent Film according to the National Board of Review (NBR). I’ve nominated it three times this year at Rich Picks, in categories including Actor in a Leading Role and Costuming, and it is now my official pick in Adapted Screenplay.

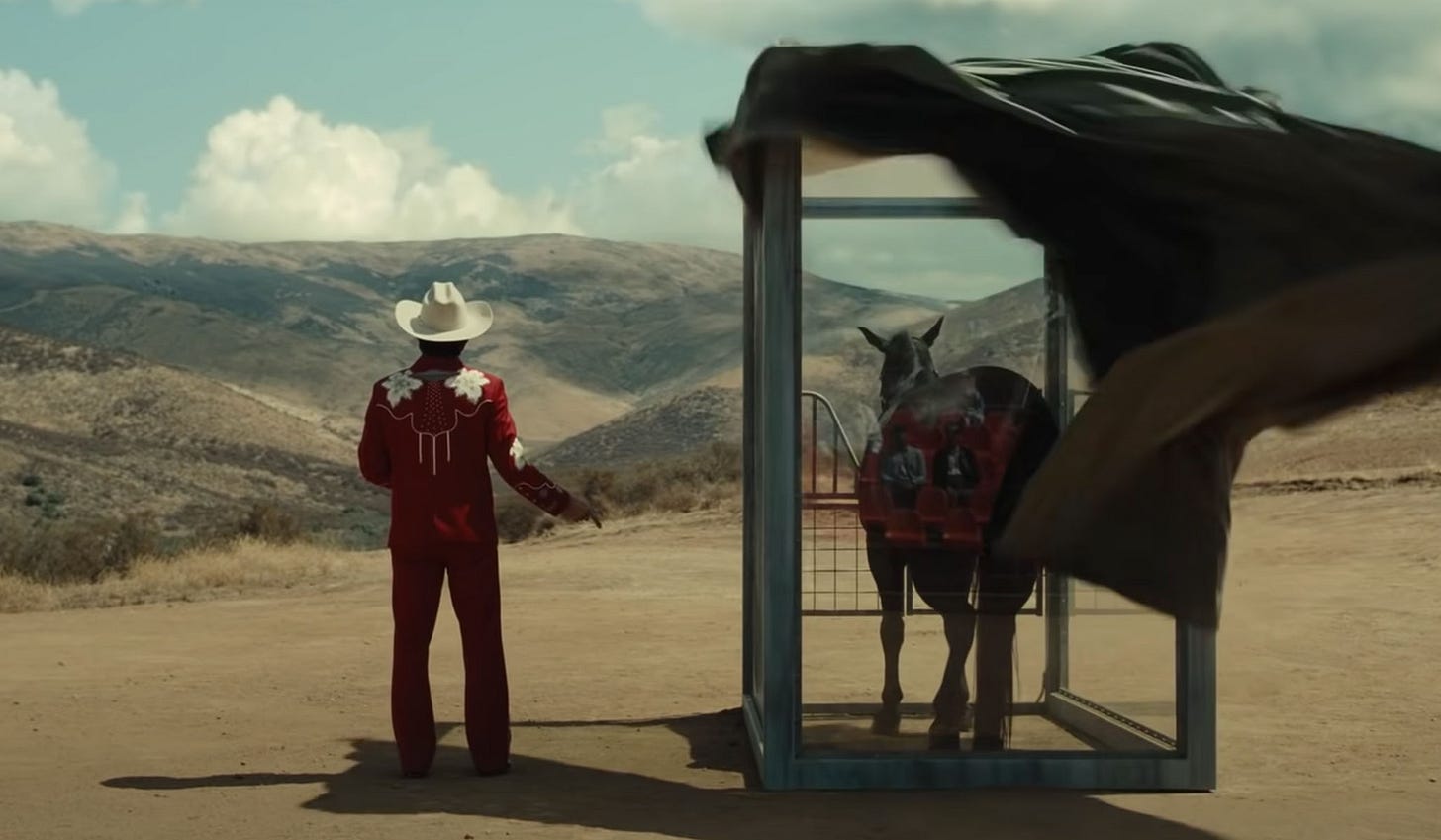

Nope

Peacock • Western • Fools Rush In Where Angels Hunt

Synopsis

The legacies of two family businesses contend with uncertain skies.

My take

For me this past year, readers, it was Nope, not Everything Everywhere All at Once, that was the early-year award-contender that could. A fiercely intelligent homage and update to the underplayed Western genre of film, Nope was in many ways for me a nearly perfect rendering of saying less and showing more. Buffeted by a gripping original score, the film, thanks almost exclusively to the mind of Jordan Peele at its helm, avoids stepping directly onto most of the tired film clichés we might otherwise expect from a supernatural Western thriller and succeeds instead by taking the audience on a careful tour around them: subtly pointing them out when they appear, then disabusing us of any notion that this story is going to be as easy to predict, and ultimately cashing in majorly with a sweeping crescendo that, like a broken dam, lets all that pent-up expectation flow majestically out into the sunset (for where else would any true Western conclude?). I basically applauded aloud in the theater, readers, and, if you happened to catch Nope on the big screen, I’ll suspect you did too.

Referring directly to cultural touchstones like Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Spielberg, 1977), Stagecoach (Ford [dir.] & Nichols [wri.], 1939), and The Twilight Zone (Serling [creator], 1959) among others, Nope knows where it comes from and where it’s going. But, importantly, even if you’re not a person who can pick out those references for yourself upon viewing, Nope is still a film that strikes you subtly with its imagery, sound, and scale. It is nearly literally biblical, and it leans into that identity in the best way.

If I were to detract from the film in any way, it’d be only for its acting performances, which — with the stark exception of Steven Yeun’s haunting supporting turn that genuinely nearly made it into my Top 5 Supporting Actor performances of this past year — I found mostly just adequate representations of what was on the page.

Otherwise, truly, readers, in my book Nope meets if not exceeds expectations. Would only that the Academy had long and wide enough memories for two films from the earlier part of last year.

Nope won the ‘Best Science Fiction Film’ Saturn Award from the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror Films (which specializes in these relatively unique “genre” films) and is one of the American Film Institute’s (AFI’s) Top 10 Films of the year. I’ve nominated Nope nine times this year at Rich Picks, in categories including Cinematography, Original Score, Director, and Live-Action Feature.

Temperature check

Hot

An Ostrich Told Me the World Is Fake and I Think I Believe It

Vimeo • Animation • Cogito Ergo ‘Boom’

Synopsis

An office worker begins to doubt the reality of his surroundings.

My take

Lachlan Pendragon’s quippingly titled An Ostrich Told Me the World Is Fake and I Think I Believe It is, to me, the quintessence of what animated short filmmaking is all about: wit, style, and emotion (in 40 minutes or fewer). A student’s film that has been raised into eligibility for this year’s Oscar for Best Animated Short by winning the parallel category at the Student Academy Awards in September, the piece is meritoriously intelligent, curious, and affecting. In under 12 minutes, it follows a mystifying reality-breaking episode in the life of an Australian office worker, who through a curious encounter with an ostrich begins to seriously doubt his surroundings. Exactly how he doubts them, what tests he tries to prove his theories, and what visual schematics reïnforce those tests I’ll forgo here, for the sake of not spoiling the fun, but suffice it to say that the sum of those efforts becomes the most inventive commentary on the nature of reality (in a Cartesian sense) I’ve seen over the past year, Everything Everywhere All at Once included.

Thematically related to and no doubt inspired by past features including The Matrix (Wachowski & Wachowski, 1999), Office Space (Judge, 1999), and Sorry to Bother You (Riley, 2018) but literally placed one step beyond those features in diegetic commentary on free will and the opportunity to step outside an otherwise monotonous system, the film is a neat and critical update to the cinematic discourse on conformity vs. self-determination. To its ultimate credit, where this update ends — spoiler alert — interestingly avoids the pattern of lionizing the protagonist as a “chosen one” type of hero and chooses, instead, the relatively new path of underlining the protagonist’s everydayness as a claim that, while we in the audience and he on the screen may be in different places, we both are ultimately still passive participants in the same illustrated dynamics. What a comment on casual viewership! Hitchcock himself would applaud.

Temperature check

Hot

Tár

Peacock • Drama • “Mom Is Hurt”

This entry was originally published in my last post, documenting my takes on this year’s ten ‘Best Picture’ Oscar nominees. It is repasted in its entirety here, with an italic addendum describing the film’s current highest honors.

Synopsis

A living legend in the world of classical music remorselessly wields terrific power.

My take

Todd Field is a master of character and storytelling, and Cate Blanchett is our greatest living actress. (There, I said it. Do you hear me, Meryl? “Our greatest living actress.” Yep.)

Delivering the performance of the year — ranking for me easily in the top five of the past decade — Blanchett tears up the screen as fictional virtuoso composer and conductor Lydia Tár, a woman as much her own invention as the genius idea of writer-director Field.

I simply cannot say enough about this film; it is a masterpiece of cinema, reaching a caliber of film I’d happily wait another 16 years to have the chance to see again from the mind of Todd Field. An Oscar nominee now for every film he’s made, Field is at the top of his craft, with a track record set to canonize him as one of this era’s leading creators.

In a just world, this film would be handily winning the ‘Best Picture’ Oscar and is must-see material here at Rich Reviews.

Temperature check

Steaming

Tár is a ‘Best Picture’ (or equivalent) nominee by the Directors’ Guild of America (DGA), the Producers’ Guild of America (PGA), the Writers’ Guild of America (WGA), the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA), the Hollywood Foreign Press Association (HFPA) at the Golden Globes, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) at the Oscars and is a Top 10 Film of the American Film Institute (AFI). I’ve nominated it seven times this year at Rich Picks, and it is now my official pick in four categories: Actress in a Leading Role, Original Screenplay, Directing, and Live-Action Feature. It is my Top Film of 2022.

Triangle of Sadness

Rentable • Comedy • Primal Screams

This entry was originally published in my last post, documenting my takes on this year’s ten ‘Best Picture’ Oscar nominees. It is repasted in its entirety here, with an italic addendum describing the film’s current highest honors.

Synopsis

Two models find themselves in primal distress after a luxury cruise goes awry.

My take

After Todd Field’s gobsmacking Tár (see above), Ruben Östlund’s Triangle of Sadnessmay very well be the film that tickled me the most this year, when I sat down to watch it over the December holiday break. Having at that point won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and been nominated for a few early prizes, the film stuck out as a potential, if unlikely, contender in this year’s mainstream awards season. Despite my own instant affection for it, however, I thought I knew better than to hold high hopes for it come Oscar nominations’ morning, because this film is by no means conventional Oscar nominee material. So, you can imagine my pleasant surprise when it was announced to be in contention for not one, not two, but three top awards there this year: Original Screenplay, Directing, and the all important Best Picture.

Yes, I’ll say it again, Triangle is an unusual pick for the Academy: a provocative ‘art house’ film that eschews all standard protocol in narrative film-making in favor of its own zany (though structurally immaculate) three-act journey, ranging from the crowded backstage of a Fashion Week show to the nearly deserted beach of a tropical isle. O, sure, the film does have appeal: real-life models Harris Dickinson (memorable star of prior ‘Rich Pick’ nominee Beach Rats; Hittman, 2017) and (the late) Charlbi Dean lead an international cast, which collectively and cleverly pokes fun at the image-obsessed nature of our global society and which includes, by the way, a rather salty Woody Harrelson. So, perhaps it was the visual appeal of those two leads; perhaps, the name recognizability of Mr. Harrelson to Academy voters; perhaps, the growing possibility that the Academy is entering a new era, more welcoming of international and experimental cinema (e.g., Bong Joon Ho’s 2019 ‘Best Picture’ winning Parasite, Alfonso Cuaron’s 2018 nearly ‘Best Picture’ winning Roma) than it ever was before; perhaps, simply, the memory that Östlund’s two prior films were delightful and peculiar romps; or perhaps, a mixture of all those (and other) factors. Whatever the true reason(s), the attention the Academy ultimately gave to the film seems to have been sufficient for it to leave its delightfully acid signature as a lasting impression.

Now, despite my obvious affection, I can’t say that I wholeheartedly recommend the film to all of you, readers, because, frankly, I’m not sure that all of you undeniably have the stomaches for some of its…less than appetizing scenes; but I do wholeheartedly believe that, if you are looking for what’s legitimately new in cinema, perhaps even what’s cutting through the landscape to delight (and disgust) even so mainstream an audience as the Academy, look no further: This comedy this year is your consort king.

Temperature check

Hot (ouch!)

Triangle of Sadness won the Palme d’Or at the 2022 Cannes International Film Festival and is a ‘Best Picture’ nominee by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association (HFPA) at the Golden Globes and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) at the Oscars. I’ve nominated it three times this year at Rich Picks, in categories including Director and Live-Action Feature.

Turning Red

Disney+ - Animation - Fairy Tale

This entry was originally published on 24 March 2022, in a regular installment of Hot Tea. It is repasted in its entirety here, with an italic addendum describing the film’s current highest honors.

Synopsis

A Chinese-Canadian girl contends with sudden bodily changes that her mother and aunts expect her to tame.

My take

Readers, it is SO refreshing, to see a classic-form straight-up fairy tale, replete with all the sexual subtext you could ever want or need, set in a modern context! So often our modern tales of adolescence for children come off either castrated or omitted, that we go through really long stretches without genuine bread-and-butter allegories of physical and emotional development like Disney’s new Turning Red. I was genuinely thrilled.

All the favorites were there:

the unwitting and aspiring child;

the child’s nascent sexual interests;

the beastly vs. princely objects of that interest (here, the older males she falls in love with, despite her family’s best wishes);

the overbearing mother, whose ways the child must learn and later overthrow in order to reach adulthood in her own right;

the magical objects the child uses as tools to make that personal progress…

Ugh, I could go on and on (see Enchanted Hunters: The Power of Stories in Childhood[Tatar, 2009] and other works by Tatar for a deeper discussion on this topic). They’re all there, right in place, right where you’d want them to be.

And the wonderful thing is, none of it feels rote! Part of that feeling is certainly due to the beautiful animation, the modern context, and the sensitive heart of the story itself. However, I’ll purposefully gloss over those huge lifts here in order to focus on the key, in my eyes: simply that the protagonist in this story is a girl, not a boy, though her quest remains to make peace with the animal within — and not a cushy sweet domestic animal, mind you, but a wild animal, borne from a history of passion, aggression, and bloodlust.

I focus on this detail in part because it may otherwise pass by you smoothly; it’s the film’s obvious first premise and the very first thing you learn about its story in any preview. However — make no mistake, readers — it’s the most important fact about this story in our common culture. Why, you may ask? Simply because it breaks classic associations that I’m not aware have ever been broken before in any large mainstream story for children. Essentially, it means something (in the grand sense of meaning), that we are being told that young women like young men are hormonal, sexual, smelly, and hairy creatures — even at twelve. To me, it signals specifically that our culture may be ready to confront at scale the reality that women and men (or girls and boys) share the natural human experience of active sexual development, or by extension that we as a culture ought dismantle prior notions that gender separates adolescents neatly into the pure and smooth to be protected and the rough and prurient to be supervised.

To my recollection, among prior works only Disney’s Mulan (1998) even comes close to this kind of realization, but crucially lacks joining the smelly with the champion or the horny with the honorific. Even Disney’s Pocahontas, a young woman who came of age in a community intimately tied to literal nature (consider the ‘Grandmother Willow’ character), was portrayed as a lithe and statuesque model, whose looks are as natural and fresh as her spirit and whose (head, not body) hair is as long and lustrous as the most impeccable L’Oreal model’s (Pocahontas, 1995). The change from that imagery in 1990s’ Disney main titles to this imagery of Turning Red is, concisely, progressive gender politics of the first kind. It’s huge.

And, atop a fantastic score by two-time ‘Rich Pick’ nominee and one-time Oscar winner Ludwig Göransson, several songs — all clever parodies of early 2000s’ “boy band” fluff by Billie Eilish and Finneas o’Connell — are fruit of an appropriately red variety.

Temperature check

Hot

Turning Red is a ‘Best Animated Feature’ (or equivalent) nominee by the Annie Awards, the Producers’ Guild of America (PGA), the Hollywood Foreign Press Association (HFPA) at the Golden Globes, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) at the Oscars. I’ve nominated it three times this year at Rich Picks, and it is now my official pick in Animated Feature.

The Whale

Available for purchase • Drama • Against the Tide

Synopsis

In view of his mortality, an obese recluse tries to reconcile with his estranged now teenaged daughter while he still can.

My take

I fully cried in the theater at the end of Darren Aronofsky’s The Whale, and I did not expect to. About midway through the screening, I thought to myself, “Technical achievements here for sure, but is it working at an emotional level? Dubious;” and then, while wiping away tears at the start of the credit roll, I thought, “O, Darren knew what he was setting up here the whole time.” I think that this trajectory is as complete a testimony as I or anyone could give you, to surrogate for your own potential experience while watching this film. It’s a film that takes its time to accumulate, slowly setting up some pieces on the board, all so that in a singular grand finale it can show you why it had worked so hard on disparate and seemingly misaligned corners of the map; and the experience of that finale is at last cathartic in the most ancient sense of that word: purgative, cleansing, purifying.

With that kind of ending, the film easily soared into my Top 10 of the year. It is a considerate, intelligent, and complete piece of film-making that generates a well of empathy for the kind of character who is likely both subjectively and objectively distant from most of our lives (i.e., a literal recluse) and through him, perhaps the most unlikely of places, demonstrates the strength of human bonds and the hazards of reäctive and rapid judgements of others. This demonstration, I must add, operates admirably in a way that avoids the hollow, treacly type of characterizations that would otherwise reduce the impact of such a piece to “after-school special.”

A lot of the credit for that final addition must go not just to Aronosfky behind the camera, who I think we all already knew could command nuance to great effect (see his masterpiece, Black Swan [2010], for evidence), but moreover to his cast of actors, especially Brendan Fraser in lead and Hong Chau in supporting. The heart of the film lives within their actions and words, and I appreciated their restraint in many scenes as much as I did their willingness to ‘go there’ in many, let’s say, “memorable” others.

If I were to take points away from The Whale, then, I’d do it seriously on only two related counts: the writing and the directing.

Samuel D. Hunter adapted his own stageplay for the screen here and, it seems, decided to leave the original work mostly as it was. Most of the action takes place in a single room, where there is essentially just one door through which characters enter or exit; the pacing, dialogue, and ‘action’ are hardly ever subtle per se, even if they may be quiet or everyday, so that the imaginary audience in even the back of the mezzanine of the playhouse could read everything and understand exactly what’s happening; and the events and the visuals complementarily remain matter of fact, concentrated on only the material occurrences real people in real time could show. It’s a practical play, just filmed and staged by a more intimate camera. Now, there’s nothing necessarily wrong with this approach; several films have used this sober and practical storytelling style to great effect (e.g., last year’s Mass, one of my Top 10 Films of 2021, comes quickly to mind) — and I’m not saying that The Whale uses the style poorly. All I am saying is, when translating one’s own work from the constraints of a live stage performance to the relative freedom of a recorded film, wouldn’t one want to or at least attempt to explore the unique potential of that medium as a storytelling device, beyond the potential of necessarily real-time storytelling on the stage? Where is the thinking that makes this transition from stage to screen a genuine adaptation more than a mere transplantation?

I have similar comments for director Darren Aronofsky, especially and uniquely because his past work has shown that he is already able and ready to employ unique visual and storytelling tactics where appropriate to break a story out of a strictly practical style and into a fantastical emotional register. My key example here is the set of supporting visual effects he used in Black Swan (e.g., the rippling feathers on his main character’s skin). These effects took an otherwise straightforward material thriller (that could be staged) into a transcendent dissociative fugue with profound emotional impact on the audience, and thereby demonstrated the amazing skill and control Aronofsky has as a film-maker. I was waiting, clutching the edge of my seat and hoping for a similar visual departure during The Whale, but — mini spoiler alert — none ever really came. Especially with a title and a plot as clearly about great isolation and darkness as The Whale, I could have easily seen, for example, spare interstitial scenes of tight body shots of a lone grey whale, swimming silently in the deep black ocean, shots that slowly over time grow clearer to the audience through an assembly of the prior images, as one way to uniquely depart from the material realities of the human story in the apartment and into a transcendent emotional register — not to mention an actual depicted whale’s visual co-significance with the work’s overall inspiration and conceit.

These critiques, however, are just the extra-credit challenges I would pose to an already solid film that might want to be undeniably outstanding. The Whale, I believe, is already well worth your attention this year, readers, especially if you happen to be fans of great performances in drama.

Temperature check

Hot

The Whale is a ‘Best Picture’ nominee by the Producers’ Guild of America (PGA) and the recipient of three Oscar nominations by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). I’ve nominated it five times this year at Rich Picks, in categories including Actor in a Leading Role, Actress in a Supporting Role, and Adapted Screenplay.

So, that’s my list, readers. Thanks for taking tea with me again this week. ☕️🫖😊 Did any of these films make it into your Top 10 of 2022?

Bird joke.

Ooooooh, a very exciting list! I think I’m the kind of viewer described. I think I’ll say yes to Nope, although I’ve been doubting everything since my encounter with that ostrich 🐦