Good evening, readers 🌙

Now that the 2024 Oscars’ ceremony is behind us, let’s take a concentrated look at an alternative slate for the best of the prior year: my personal Top 10 Films of 2023.

Before I dive in, I think that it’s crucial to say what most list-makers don’t take the time to say: what criteria or qualifying merits decide whether any film earn a spot on this list. Succinctly, I tie my criteria to the viewing interests of my reader and, as in every post in this Hot Tea series, in this list I mean to deliver a digest of only those titles whose cultural and cinematic worth is the highest. So, while personal liking, specific technical achievement, and/or lack of popular recognition may figure into how I talk about any film in this list, I actively try to root out all the alternative choices that would lean onto any of those other qualities too heavily. To me, a list like this one is not the place to set out mere personal “favorites” or to wax on about the technical details of an otherwise poor picture. No, the films that make it onto my Top 10 list are simply the most worthwhile overall achievements in cinema for anyone who is even only slightly interested in the art and science of film-making and at least passively participating in our larger culture. Only those films with that kind of viewer in mind, I believe, make a good guide for any traveller in our great film landscape.

Now — one last proviso — because some great 2023 films have already appeared in prior servings of Hot Tea, wherever the films in my Top 10 overlap with takes I’ve already given I’ll mostly refer you, readers, to what I’ve already said by both linking to and reposting those original thoughts. (Don’t worry, avid followers, however; there are certainly new entries here too.)

Without further ado, I present my ‘Top 10 Films of 2023.’

Films are presented in alphabetical order.

All of Us Strangers

Hulu • Romance • Licking Old Wounds

Synopsis

A lonely writer marinates in conversations he wishes he had with people close to him.

My take

It feels quite hard, in a culture that’s experienced fewer films (mainstream or otherwise) about healthy or at least eventually successful gay relationships than films about the Holocaust, to fully digest a new film like Andrew Haigh’s 98% gutting All of Us Strangers with any semblance of honest pleasure. It’s hardly the warm hug of young entanglement, for example, Love, Simon (Berlanti [dir.], Aptaker, & Berger [wri.], 2018) was a few years ago, a film that to its own mark went down like the gay cinematic equivalent of a glass of warm milk next to a bedtime story; but then does it really need to be? And, for that matter, why was it such a landmark cinematic event when Love, Simon put forward an actually optimistic gay romance1 into the mainstream? Is All of Us Strangers’ gay desperation on a knife’s edge between interminable solitude and dewy-eyed fantasy the applause-worthy epitome of our queer cinema?

Of course, one could easily argue that All of Us Strangers, born of Haigh’s own consciousness — that is, of the lived experience of a gay man born in a certain recent decade — is just replicating its parentage: owed to the same starving culture;: like parent, like child. But that perspective ascribes little inventiveness or creative talent to the man whom Dan Levy (in one of those endlessly charming Criterion Closet YouTube videos) called a first to depict gay men seeking and finding love as just normal people doing human things (“no special gloves”).

So, what are we to think, Andrew, of this your latest invention?

Should we wallow, aggrieved of the increasing disconnection that queer people especially have experienced while maturing in our still adolescent social culture, in which Love, Simon is tantamount to a public event?

No, that feels wrong;

actually reading the text of All of Us Strangers for what it is, we know that’s wrong. (I did say “98% gutting,” didn’t I?)

Well, then should we celebrate the production success of a fairly authentic gay love story written and directed by a gay man and starring a gay actor in the (mainstream?) American cinema?

No, not exactly that either: too chipper and too reductive, like accepting with glee a participation award for showing up crying ‘on the day.’

Well, what then??

Readers, I say, let’s debate it openly — its highs and lows, its pros and cons, its merits and its flaws… — because, for me, readers, Haigh’s greatest success in this latest venture is not the first wave of demographic-relevant reactions we en masse may experience or even require for our own common sense of self, but is instead the mosaic of experiences and reactions (even and especially from outside the queer community) that lend the film, like any other ‘contender’ especially during the awards season, presence in those regular discussions among pundits, bookies, and casual theater-goers alike. Haigh has made a fairly good film— just fairly good — and, although it does explicitly deal with uniquely queer issues (including coming out to one’s socially conservative familiars), its greater mastery by far manifests in how uniquely un-queer it feels.2 In my view, this distinctly unqueer presentation comes from how deftly Haigh writes the romance that Andrew Scott and Paul Mescal’s characters develop throughout the film: simply, unpretentiously, without the “special gloves” Dan Levy so memorably spied on the hands of so many other ostentatiously “gay” films of yore that also wanted to touch even just the beginnings of a romantic connection between two members of the same sex. This is the Haigh I know and treasure: 100% unostentatious, the leading figure in the ‘new’ queer cinema, wherein people people— full stop.

Ultimately, the scrap of hope Haigh imbues into the final frames of his narrative about — spoiler alert — grief and acceptance isn’t really enough here to fix the two fundamental problems in its runtime (i.e., noir, Andrew? and at what cost?), but no matter: we need not a flawless film; simply that there is hope in the new queer cinema at all and that it meets no special treatment are still enough for now.

All of Us Strangers is a Top 10 Independent Film according to the National Board of Review, was nominated for: Outstanding British Film, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Supporting Actor, Best Supporting Actress, and Best Casting at the 2024 BAFTA Awards; Best Film, Best Director, and Best Actor at the 2024 Independent Spirit Awards; Best Adapted Screenplay at the 2024 Critics’ Choice Movie Awards; and Best Actor in a Motion Picture - Drama at the 2024 Golden Globe Awards, and took home the awards for Best British Independent Film, Best Director, Best Cinematography, Best Editing, Best Screenplay, and Best Supporting Performance at the 2023 British Independent Film Awards.

Andrew Scott, Paul Mescal, and Claire Foy were all Rich Pick nominees this year for their performances in this film.

Temperature check

Hot

Barbie

Max • Comedy • Material World

This review is a reproduction of the original, published in the 30th serving of Hot Tea on 27 February 2024. It’s reprinted here in its entirety, to represent this film in my Top 10 of 2023.

Synopsis

Infraction in the real world ripples through the idyllic anesthesis of Barbieland.

My take

Greta Gerwig continues to impress with this nearly seamless moral comedy of manners on modern gender roles and expectations. A feast for the eyes as well as the ears, Barbie is the punkily anti-corporate intellectual diagram of ‘where we are now’ and ‘how we got here’ no one would ever expect from so mainstream an adaptation of an iconic $1,490,600,000 brand (Mattel, 2024). Rich with cinematic references (see Dockterman, 2023, for a run-down) and two fascinatingly sharp central performances (of two extremely formidable-on-paper characters, mind you; see this clip from Margot Robbie’s “Actors on Actors” conversation with Cillian Murphy for more on this topic), Barbie is clearly the film that should by all accounts be expecting to take home the ‘Best Picture’ Oscar this year, simply because it is genuinely the one film that most successfully marries the roar of the popular cinema with the hush of any expert film-craft.

But, I suppose, if those of us who have already seen Barbie truly paid any attention to its most basic message, we'd already know — well in advance of this month or even the fall film season — that, if any film from the 2023 summer blockbusters will actually walk home with the ‘Best Picture’ prize, it won’t be Barbie herself but her box office husband, of course, immediately deemed a much more “appropriate” winner. Now, why could that be…?

Barbie did lose the 2024 ‘Best Picture’ Oscar to Oppenheimer (Nolan, 2023) but, I think history will acknowledge, remains the stronger and more impactful film of 2023 by far.

Barbie was nominated for seven Oscars and took home one, for Best Original Song; five BAFTAs, including Best Actress in a Leading Role and Best Original Screenplay; and sixteen Critics’ Choice Movie Awards and took home six, including Best Original Screenplay and Best Comedy.

The film is also a six-time 2023 Rich Pick, for its leading performances, costuming, production design, original song, and adapted screenplay.

Temperature check

HOT!

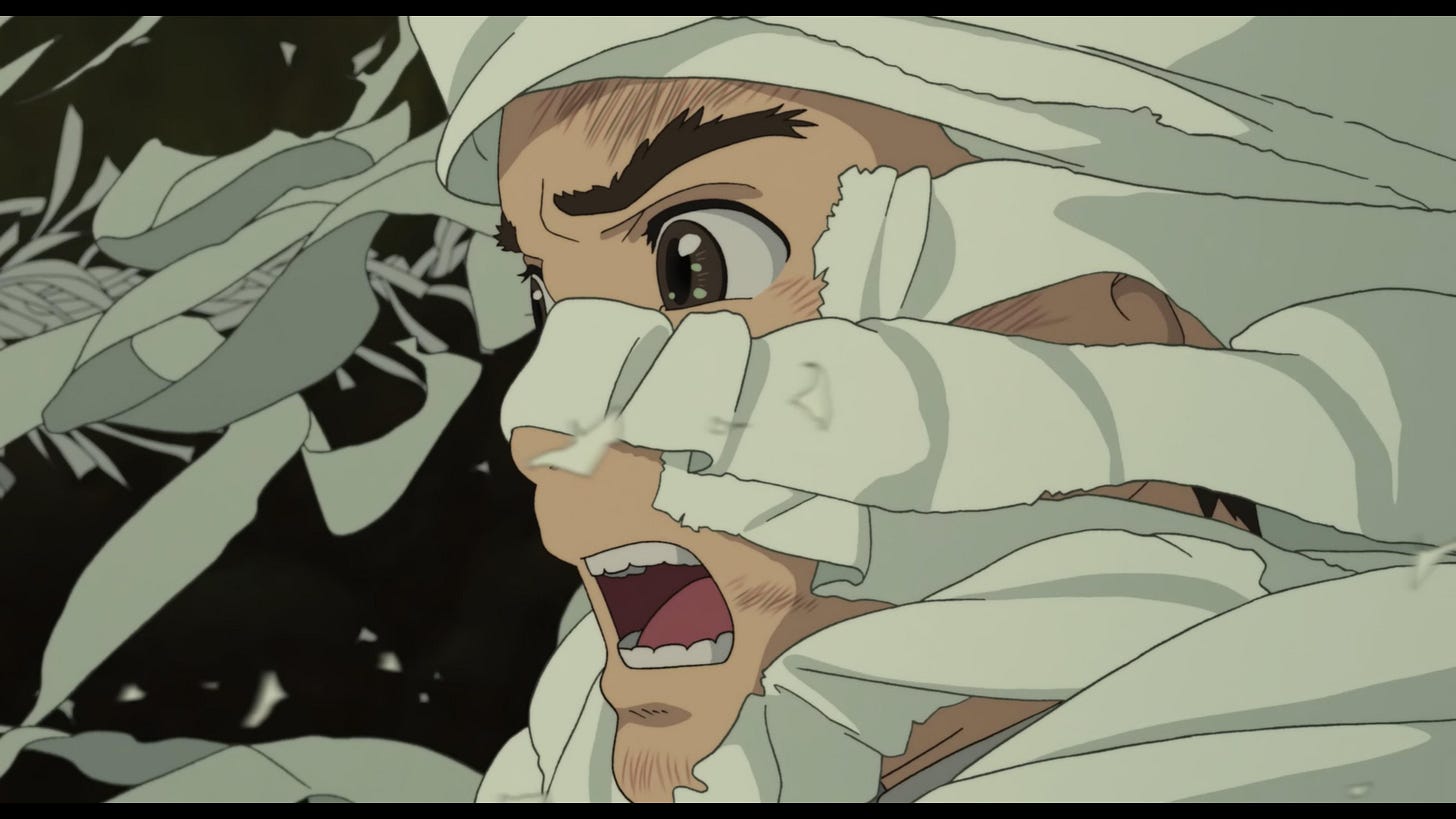

The Boy and the Heron

Rentable • Animation • Maturity Isn’t What It Seems

Synopsis

Left mostly to his own devices, a boy on the doorstep of maturity picks apart the world around him to find a truth he feels strong enough to stand on.

My take

Defiance, that intrepid presentiment of flying consciously into the face of expectations or demands from others, is Hayao Miyazaki’s distinct signature, unifying characters across his films, from Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) through Spirited Away (2001) to his latest, The Boy and the Heron. As his signature, this defiance is a consonant feature of Miyazaki’s worlds, by design unmovable and unshakable unless pushed — no, shoved — by intentional individuals who can recognize unmet needs and unexpressed desires (perhaps inarticulately but nevertheless accurately) and somehow alone can choose to edify or dismantle them. It is the filmmaker’s burden, or at least it is according to Miyazaki himself; and, while his Spirited Away remains so far the greatest expression of this philosophy’s natural tension against emotional maturity and emotional intelligence, here, in The Boy and the Heron, the filmmaker takes the consequences of using defiance, like an arrow shot through a veil, farther than he has ever taken it before and consequently finds an articulate beauty in the most adult description of adolescence he has ever ventured to deliver to his audience, a description soaked heavy in the sweat and tears of mortality.

It’s not really a spoiler to say that The Boy and the Heron begins with a dramatic loss. The first several minutes of the film are a nightmare of tragedy, as the protagonist, while still a very young boy, finds himself powerless to stop the literal fires of war from endangering his own life and consuming his mother’s. The imminence of this very real physical danger doesn’t deter the boy, especially at first; in defiance of his father’s orders and defiance of his own instinct to remain safe, Mahito sneaks away from his home in search of his mother in the blaze. This small act of defiance is — now, spoiler alert — the premise of and stage for the entire rest of the film; motherless in a new reality away from the city he knew, Mahito makes choices that reify defiance as a way towards self-knowledge and personal autonomy, however arduous that path may be along the way to those freeing destinations. The unflinching mortal backdrop to this journey toward adulthood is a step forward for Miyazaki’s films; while of course the protagonists in his films have hardly ever been strangers to extreme loss (e.g., Chihiro temporarily loses her parents and her place in the world and nearly also loses her identity, Ashitaki fears losing his own life after being poisoned by a rabid boar while Mononoke fears losing the life of the forest that reared her, Sophie loses her youth while helping Howl rediscover his heart…), the difference here is the permanence with which Mahito’s loss is etched into the reality of the story. Unlike all of those other protagonist’s journeys forward, Mahito’s is one toward acceptance of a permanent reality, one irreversibly marked by loss and the necessity of grief. Perhaps, in this expression of his consistent efforts on defiance, we in the audience can sense a bit of the storyteller’s coming to grips with his own history and his own mortality; The Boy and the Heron was never supposed to be a film Miyazaki made, but became one he did make by the sheer weight of his creative desire to still explore the human condition, via his condition, which he himself knows best.

In this advancement of his own long-standing artistic legacy, The Boy and the Heron provides perhaps some of the most beautiful and frightening passages in all Miyazaki’s animated stories. Never forgetting the beauty of innocence, growth, and acceptance, the film is a love letter to a past self, one he perhaps never actually knew but passionately nevertheless lived beside him; a farewell to the mother of an idea that began maybe forty years ago with Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind; and an embrace of whatever new adventure the bravery of that knowing acceptance of a life one can no longer live may come to offer. For this bravery, for this beauty, this film is in my book hands-down the best animated film in recent memory and certainly one of the ten best films of 2023.

The Boy and the Heron won the 2024 Oscar, BAFTA, and Golden Globe awards for Best Animated Feature and is the 2023 Rich Pick for Best Animated Feature.

Temperature check

Hot

Eileen

Rentable • Thriller • Confusion

Synopsis

Attracted by her unusual self-possession, a meek functionary finds outlet in a new colleague’s ability to own the rooms she enters.

My take

William Oldroyd’s cinematic retelling of Odessa Moshfegh’s (2015) novel was a stand-out for me at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival early last year. Literary in impression, with a gothic feeling from its memorable original score, the adaptation packed just enough of a punch to see itself over the hump of what otherwise could have been an overwrung cautionary tale about the modern siren’s song.

The siren? A character named Rebecca St. John, played with verve by a very convincing Anne Hathaway, who stirs up the dried leaves in the doorway of the eponymous Eileen’s life — for better or for worse is up to the audience to decide.3 It’s a classic dark fable, penned with eager admonition for any impressionable reader to tuck safely into a file cabinet of personal “Dos and Don’ts.” What it adds to that classic history is the layer of exclusively female desire it centers in its plot, commenting necessarily on the politics of admiration within one’s own sex, the practice of aspiration in the larger world, and the precipice between self-tyranny and self-love any woman (or man for that matter) can recognize. Away, Odysseus and his intrepid male crew; here, the only men stay behind bars.

And, as an actors’ director, Oldroyd hems the garment close to the model: Culpability is just couture one can choose to or choose not to wear, and he clearly tailors his storytelling to look best on each of his two central performers. I won’t say that the end result is an absolute triumph — Eileen could do with another smoothening pass, if you ask me — but I will say that I find it unjust that so few end-of-year lists and conversations have included this tiny opaque gem in their praises of 2023 releases. Cinematographer Ari Wegner, whose prior work on Jane Campion’s (2021) The Power of the Dog earned him Oscar and Rich Pick nominations, paints a haunting jejune palette that helps this story shine; and Richard Reed Parry’s matching score earned a Rich Pick nomination.

Actresses Anne Hathaway and Marin Ireland and director William Oldroyd each received a nomination for their work on this film at the 2024 Film Independent Spirt Awards.

Temperature check

Tepid (only because it’s a bit niche)

The Holdovers

Peacock • Comedy • Letting It Go

This review is a reproduction of the original, published in the 27th serving of Hot Tea on 17 January 2024. It’s reprinted here in its entirety, to represent this film in my Top 10 of 2023.

Synopsis

A curmudgeonly teacher at a New England boarding school reluctantly redresses lapses in the educations of students whose parents left them alone over winter break.

My take

Da’vine Joy Randolph is poised to win the Oscar this year for her thrilling supporting work in Alexander Payne’s new film, The Holdovers.

The first Giamatti-Payne collaboration in nearly 20 years (since the pair inimitably collaborated over Merlot in Napa Valley; see Sideways, 2004), it is a thrill to see the two at work together again. Giamatti’s Paul Hunham is a perfect fit for the actor’s talents: a shrill, sheepish, tyrannical, compassionate, insensitive “student of the old guard” who issues Latin from a lectern with as much concentrated fervor as a laser from a high tower — the man must have been such fun for Giamatti to play! For his efforts, I wouldn’t be surprised if Giamatti too walked away with more than one golden trophy this awards season.

However, the queen of this film is, indeed, Da’vine Joy Randolph herself. Rendering a heartbreaking performance as an aggrieved mother on staff at the boarding school where Giamatti’s Hunham teaches, Randolph swims with articulate finesse through both the shallow and slow and the deep and choppy waters her character as written must cross. Perhaps more than any other supporting performance this year — from a male or female actor — she made me believe that she WAS that character; and the emotional story of her arc on paper, when followed with such fidelity, becomes its own reward.

Beyond these central performances and the capable hands Payne and his screenwriter David Hemingson used to respectively direct and pen them for the screen, The Holdovers shines most and best via its depiction of setting: the careful yet expansive designs of the production, the period-perfect make-up and hair, and the tinted cinematography, which together instantly convey the time and feel of the action in each scene. One needs only the single frame of the boys with long shaggy hair in loosened ties amidst the frosty tundra of December’s New England, to understand instinctively the where and the when of the environment.

Certainly a personal Top 10 film this year, The Holdovers is well worth the watch.

Da’vine Joy Randolph did win the 2024 Oscar, BAFTA, SAG, Golden Globe, and Film Independent Spirit awards for her performance as Mary Lamb in The Holdovers, which was additionally nominated for four Oscars, including Best Picture; six BAFTAs, including Best Film; seven Critics’ Choice Awards, including Best Picture; three Film Independent Spirit Awards; the DGA award; the PGA award; and the WGA award and is a Top 10 Film according to the National Board of Review.

The Holdovers is also a five-time 2023 Rich Pick nominee and is the 2023 Rich Pick for Actress in a Supporting Role.

Temperature check

Hot

Origin

Rentable • Drama • Common Histories of Oppression

Synopsis

A writer’s own story of loss complicates her research on the common subjugation otherwise historically divergent societies have practiced to terrific effects.

My take

There’s an understated elegance to Ava DuVernay’s Origin; it seems to know that its point is better made quietly and deliberately than shouted aggressively or insistently. Wise here in this way, DuVernay earns my respect through this film after, frankly, lackluster, off-beat, or simply poorly executed features of the past.

A large part of this shift in the quality of DuVernay’s work is likely attributable to two factors: the source material she adapted and the leading actress she cast.

Though I was and I remain unfamiliar firsthand with the text of Isabel Wilkerson’s (2020) Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents except through its presentation in this film, my understanding of its arguments, which are philosophically complex and initially surprising (I’d bet, surprising to anyone sufficiently rehearsed on the pre-existing scripts of our sociopolitical consciousness), felt to me undiminished in their power by their translations onto the screen. If anything, the thread Wilkerson and by extension DuVernay weave, tracing complicit subjugation through Black history in America, Jewish history in Europe, and Dalit history in India, appeared more alive than ever, given real human form on screen, and strung together pieces of a larger, global sociopolitical phenomenon that previously shared no connective tissue except the adjoining label of assaults on basic human dignity.

DuVernay chooses wisely to make Wilkerson’s arguments personally, invoking the author’s own story as her own connective tissue and the explicitly subjective lens she’ll use to show us the otherwise disparate strands of oppression the rest of the film explores. This notably subjective perspective may be DuVernay’s smartest narrative choice, because it decidedly complements the strictly non-documentary approach her and Wilkerson’s story takes: With vivid imagery that touches or strikes at the audience’s heart, DuVernay allows herself, her actors, and her source material to find the human expression it needs in order to function not as a report, but instead as an essay. And thanks for the successful reading of this essay must then go in huge part to the work of the cast, especially leading actress Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor, whose sleek, grounded, empathetic, and thoughtful performance whiffs of what I admired so heavily two years ago in Nicole Kidman’s performance of Lucille Ball, though here to a far different effect.

While the complete translation from page to screen isn’t perfect, the quasi-kaleidoscopic montage of anthropological sense-making through human stories that does make it onto the screen assembles a beautiful approximation of the technical arguments Wilkerson’s original text appears to make by trading only their scholarly descriptions for sincere individual truths. It is the grace of this film, the elegance I mentioned at the top, that these sincere individual truths find sincere individual expressions in the acting from the cast in general — but from Ellis-Taylor and Audra McDonald in particular.

While Origin may have flubbed its distribution (coming out too late and too sparse in the season to really land on the “big” awards’ lists), I’m glad I made a point of including it in my review of the season, because its emotional strength is a significant addition to the year in film.

A NYTimes Critic’s Pick, Origin competed for the Golden Lion at the 2023 Venice International Film Festival and won the 2024 awards for Best Drama, Best Director, and Best Actress from the African-American Film Critics’ Association.

Origin is also a four-time 2023 Rich Pick nominee, including for Live-Action Feature-Length Film.

Temperature check

Hot (particularly if you enjoy social theory)

Pachyderme

Rentable • Animation • Recovery

Synopsis

A woman recounts the summers she spent with her grandparents in the countryside.

My take

Stéphanie Clément (dir.) and Marc Rius’ (wri.) metaphorically violent Pachyderme reminded me of some of the great short stories I’d read studying literature: Guy du Maupassant’s (1884) La Parure, Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s (1892) The Yellow Wallpaper, Edgar Allen Poe’s (1843) The Tell-Tale Heart… It’s not just that, like those short stories, Pachyderme is itself a short; it’s much more that, like those short stories, Pachyderme applies no boundary between the experience of the protagonist and the experience of the world around that protagonist. Like a blooming flower in a potting soil, the two are intricately interlinked, highly co-dependent and variable, and complicit with one another’s features. Pachyderme’s protagonist feels and feeds echoes of herself in the world around her, swimming where the reeds stretch and bend with her hair, submerging under the surface to remit any division from the world beneath, and literally fading into the swallowing floral wallpaper in her bedroom. The floorboards creak only in reference to her own emotional weight and uncertainty. The semi-transparent appeal of these connected gestures is Pachyderme’s own living tissue writhing in your very hand; just as readers felt the thump of Poe’s protagonist’s mounting guilt, so here we viewers feel the retreat of Clément and Rius’ protagonist from her mounting fear. Though nothing escapes this feeling into express statement, we can’t help but leave with an intuitive knowledge of the source of this character’s distress and the individual peace she later made as an adult with that dilemmatic but inescapable context. Thrilling because of this skillful inspiration of disquietude via its otherwise idyllic grandparental summers, Pachyderme is the sleeper hit of 2023 film.

Pachyderme was nominated for the 2024 Best Animated Short Oscar and is the 2023 Rich Pick for Best Animated Short.

Temperature check

Hot

Saltburn

Amazon Prime • Drama • Satyricon

This review is a reproduction of the original, published in the 26th serving of Hot Tea on 8 January 2024. It’s reprinted here in its entirety, to represent this film in my Top 10 of 2023.

Synopsis

An unassuming university first-year sees potential in a budding housemate, despite — or perhaps because of — a difference in social class between them.

My take

Readers, it feels only right, to begin this newest serving of Hot Tea with what I declare is the most discussed new film of this past cinematic year: Emerald Fennell’s strikingly decadent Saltburn. That Fennell’s Saltburn is decadent, a textual and visual feast of a certain kind, is, no doubt, what has made the film the subject of discussion: Audiences have no trouble with agreeing that the film is ambitious and iconoclastic, particularly against the violent excesses of the über-wealthy, the patriarchal halls of their inherited privilege, and the timeless fascinations of the male gaze onto specifically undressed female bodies, and can’t contain themselves from vaunting all vantages on such topics on social media; AND audiences then diverge sharply when confronting what those qualities mean, or indeed whether they mean anything, incidentally making Saltburn(somewhat beguilingly) the subject of mass and occasionally heated debate. Is Saltburnan “empty beauty,” all gaze-drunk panache with no purpose, or is it OK for beauty to exist for beauty’s sake alone? Of course, readers, we know that it’s never quite that simple.

Let’s start our response to this mass debate by defining Saltburn’s “decadence.” Working with cinematographer Linus Sandgren — whose work we may already know from his Oscar-winning La La Land (2016) or even his ASC-nominated First Man (2018) — Fennell delights our eyes with purposefully cropped, 4:3 overtures that she marks staccato with what would elsewhere be 16:9 études, to shape the tone of the film: a resonant series of chords vacillating on a knife’s edge between what is real and what is possible. Dreamy, fantastical images transfigure the real lives and grounds of especially the titular location, a countryside estate named ‘Saltburn’ where the central characters repose with family during holiday, into a byzantine, nearly chimerical, but always alluring paradise — particularly, a paradise of the sort many a person who’s long had to “sing for one’s supper” idealizes from the outside but fails to fully understand on the inside, perpetual thanks to its proprietors careful cuts around its borders. That end place, that haven, is the laboriously dull end to all actual labor, the full life of luxury on the backs of staff, the idyllic privacy of expansive personal holdings, that voluminous sacristy where everything is unequivocally at one’s disposal and no one else’s.

The critics, I’m sad to say, leap from receiving this “decadence” directly into claiming its insubstancy: how vapid the show is, a feast for the eyes but not the mind, even cultural pornography.

“If you see it as a lurid pulp fantasy rather than a penetrating satire, then Saltburnis deliriously enjoyable” (Barber [for the BBC], 2023). Translation: If you ransack the movie of all its substance and/or just turn off your brain, then it’s great!

“Saltburn looks divine […] but they’re working with paper-thin characters” (Butcher [for Empire], 2023).

“‘Saltburn’ is the sort of embarrassment you’ll put up with for 75 minutes. But not for 127. […] The thing […] doesn’t have many thoughts and even fewer feelings. […] It’s another music-video fantasia” (Morris [for The New York Times], 2023).

Perhaps worse, the advocates, on the other hand, decry affronts to the film’s quality on the feeble grounds that spectacle is spectacle and they should be allowed, if not encouraged, to see it.

“Saltburn is a really exciting and excited filmmaking piece. I didn't demand of it a moral fable- it was a skillful, audacious and obsessive grotesquerie- a Steadman, a Hogarth- a state of being, remembered by an unreliable narrator- heightened by his memory & desire.” -Guillermo del Toro

For my part, readers, both groups are missing the point. The whole debate is as if people read — no, not “read” — paged through The Great Gatsby (Fitzgerald, 1925) and then came away fervently with either the pro or the con side of the common take, “Wow, parties.” What am I even saying? People have done and continue to do exactly this kind of reduction in memory of Gatsby all the time; the mere existence of any Gatsby-themed party is sufficient to say so. So, perhaps I shouldn’t be as surprised as I am, to see almost no one taking a different view.

To both sides, I say unflinchingly, your reading of this film lacks awareness and attention. Knowing what I know about film and about our current culture, I actively applauded aloud in the theater the moment the credits started to roll. “Emerald did her homework!” I remember exclaiming and then instantly starting to jot down thoughts for this very take, thoughts starting and ending with a list of 12+ films I saw Fennell and her collaborators on this film actively referencing, to firmly plant this new film within existing conversations and to clearly document how and where it departs from those already available points of view.

The Talented Mr. Ripley (Minghella, 1999),

Get Out (Peele, 2017),

Lolita (Kubrick, 1962),

Maurice (Ivory [dir./wri.] & Hesketh-Harvey [wri.], 1987),

Call Me by Your Name (Guadagnino [dir.] & Ivory [wri.], 2017),

Dead Poets Society (Weir [dir.] & Schulman [wri.], 1989),

Last Year at Marienbad (Resnais [dir.] & Robbe-Grillet [wri.], 1961),

The Line of Beauty (Dibb [dir.], & Davies [wri.], 2006),

The Long Day Closes (Davies, 1992),

The Shining (Kubrick [dir./wri.] & Johnson [wri.], 1980),

Bright, Young Things (Fry, 2003),

Heartbeats (Dolan, 2010),

The Social Network (Fincher [dir.] & Sorkin [wri.], 2010), and

Parasite (Bong [dir./wri.] & Han [wri.], 2019)

— not to mention all the more classical or literary ancestors whose genetics also live within Salburn (e.g.,

Vanity Fair [Thackeray, 1847-1848],

A Midsummer Night’s Dream [Shakespeare, ca. 1595],

Theseus and the Minotaur [Ovid, 8 — or even Canova, 1781-1782]

) — all have specific signatures Fennell and her team actively use to situate their protagonist’s story within a cultural lexicon of others like his, each time building on the memory of its forebears and each time responding to the stresses and priorities of its era. Specific visual memories such as The Talented Mr. Ripley’s bathtub, Lolita’s picnic, and Last Year at Marienbad’s built environment resurrect sociocultural dialogues about homosexual intimacy, the male gaze, and subjectivity in the lens, dialogues that Saltburn actively advances by writing each signature beyond mimicry, into legacy. Yes — spoiler alert — Barry Keoghan’s performance does show him cravenly slurping at the dregs of Jacob Elordi’s masturbatory bathwater BUT does so as a direct response to the silenced restraint Matt Damon’s performance requires despite his own lavatory desires for Jude Law’s drippings in The Talented Mr. Ripley. Yes, Sandgren’s camera lingers on Elordi’s character’s insouciant sunbathing with a popsicle BUT does so as a direct response to Oswald Morris’ camera’s lingering on Sue Lyon’s own summery repose with a lollipop in Lolita. Yes, Saltburn’s property and gardens loom and beckon pornographically (Morris, 2023) but do so in direct conversation with the subjectivity that lent grand mystery and complexity to the resort featured in Last Year at Marienbad. I could go on, but I won’t, because the point I think is already made: Not idly or subconsciously do these coincidences of textual if not visual memories arise in Saltburn; the film is actively engaged in provoking what comes next in both the core texts of these stories as metaphors for social practices and human motivations and the meta-text of the metaphors themselves as semiotics within a shared social consciousness.

Fennell’s greatest victory here then comes not merely from her scholarship and bibliography, which themselves are immensely praiseworthy, but rather directly from the fact that she speaks through Saltburn using a shared social lexicon that, by definition, we need not explicitly manifest to understand. The ‘trick’ for us in the audience is only to not forget to pay attention to it. So, yes, if you watch even just a 30-second advertisement of Saltburn you can already tell that it entails critiques of especially inherited wealth and stature; but if you watch the whole film, I can’t understand, how could you ever come away with thinking that that’s where the critique ends? Protagonist Oliver Quick is not — spoiler alert again — a noble character, Dickensian in any way, or laudable to anyone except those who read him like Jay Gatsby in a single flimsy glance. The audience isn’t supposed to like him or anyone in the entire film. Every single character is a terrible person, a tax on the social system, each uniquely awful in his or her own way and each then present for a similarly unique purpose in Saltburn’s true commentary on our times. Yes (among other points), Saltburn agrees, the generationally wealthy can very well be detached and ignorant BUT, it goes on, the greater culprits in our present world may actually be the bourgeoisie, the upward reaching middle and working classes whose members admire if not worship the generationally wealthy in the same breaths in which they revile them. Consequently, present obsessions with money, fame, and glamour eat away worse than anything else at the bedrock of a capitalistic society — and do so not least because desires for those ends are so pervasive and relatable as to literally pass notice of every Saltburn critic or advocate I’ve so far come across. So, while achieving any one of those ends in life may indeed call for a dance in the minds of most people, it is, Saltburnclearly argues, ultimately a danse macabre, performed alone.

I could say more — much more here, readers, about Pike’s exceptional performance, the deft costuming, the music… — but suffice it for us now, for me to say simply, Saltburn is easily the best film I have seen this year or expect to see the remainder of this awards season. Bravissima, Emerald! Please, don’t stop.

Saltburn won the 2024 Art Directors’ Guild, Costume Designers’ Guild, and Make-Up Artists and Hair Stylists’ Guild awards for excellence in contemporary work in all three domains and was a five-time nominee at the 2024 BAFTA Awards, a three-time nominee at the 2024 Critics’ Choice Movie Awards, and a two-time nominee at the 2024 Golden Globe Awards, including for Best Actor in Motion Picture - Drama.

Though very nearly surpassed by Jonathan Glazer’s (2023) The Zone of Interest, Saltburn remains the 2023 Rich Pick for Live-Action Feature-Length Film as well as Original Screenplay.

Temperature check

Steaming

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar

Netflix • Fable • The Pursuit of Happiness

Synopsis

An author recounts his knowledge of the transformation of an unprincipled idle gambler into a remarkable philanthropist through connected personal tales.

My take

Albeit a specific kind of sadness that Wes Anderson’s feature-length 2023 film Asteroid City frankly pales in comparison with this gem of a 2023 short, the writer-director’s astute eye and ingenious style nevertheless work to great effect here in bringing to life Roald Dahl’s charming (1977) short story The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar. Thanks in large part to genuinely stellar performances from Ralph Fiennes and Benedict Cumberbatch, whose efforts make the concocted pretention of meticulously reticulated angles and nearly monochromatic colors decidedly human rather than machined, the film is an entrancing joy from start to finish.

I see two key reasons for this great success:

Anderson’s distinct, highly fantastical style is here obviously intentionally applied to a suitable substrate: a distinctly fantastical children’s story. Like a hand in a glove, the pair fit each other with an aplomb that even the audience from the outset can share.

Perhaps because the film is a short, the size of the task of fully milling it into a nearly perfect shape is just fundamentally easier than the task of similar milling a full-fledged feature. There’s just less to do — especially when all the beats and tones have already been so finely worked out not just by Anderson and his crew themselves, whose preparatory work I have no doubt is extensive and thorough on every project, but also and moreover by first Dahl himself, whose own peculiar taste for fine lines and specific brevities clearly had manicured the plot of this story to a sharpened point just like that of the six notable pencils his character extols having on screen.

Whatever the true reasons, it remains obvious to me, the complex choreography of acting and elaborate origami of sets any remotely familiar viewer could easily identify as stylizations belonging to Anderson haven’t been in as fine a form since his (2014) The Grand Budapest Hotel, the Rich Pick for Best Film in its year. In short — how appropriate! — Anderson achieves a melody of rampant but tamed dialogue atop the percussive rhythm of narrative momentum driving this story forward that filmmakers I think hope to achieve in rendering any final work before an audience. Rehearsed, clean, polished, The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar is peak Anderson and, good news for us, peak cinema this year also.

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar won the 2024 Oscar for Best Live-Action Short and is the 2023 Rich Pick for Live-Action Short Film.

Temperature check

Hot

The Zone of Interest

In Theaters • Drama • The Banality of Evil

This review is a reproduction of the original, published in the 30th serving of Hot Tea on 27 February 2024. It’s reprinted here in its entirety, to represent this film in my Top 10 of 2023.

Synopsis

An officer of the Third Reich, his entitled wife, and their insouciant children live bucolic lives just on the other side of the wall from the Auschwitz concentration camp.

My take

Jonathan Glazer is one of our greatest living filmmakers. His Birth (2004) and his Under the Skin (2013) already lived vividly in my memory as masterpieces of the form, well before I sat down in the theater last month to see his latest film, The Zone of Interest. It’s more than that his past films were great; other directors’ films were and are great and still fail to intelligently push the boundaries of style and symbolism narratively and technically the way Glazer’s films have. To see Birth or Under the Skin is to have a simultaneously elegant and unsettling experience that disabuses you of unnecessarily limited notions of how form, color, and music can be combined to deliver narrative and emotional impact on the screen, or did so so memorably for me that my understanding of the cinema forever changed from those first viewings.

So, it was with no small satchel of expectations that I tucked myself into the theater last month, to (at last!) see his latest work — a pleasure that seems to transpire only once every ten years! — and, readers, I was in no way disappointed. Glazer once again brings his inimitable eye and narrative voice to this unique, harsh, and ultimately horrific historical fiction about the life of the officer stationed in charge of operations at the Auschwitz concentration camp. Alongside his wife and their several children who all enjoy the privileges of that station with the blissful ignorance of any aspirational housewife and her liberated brood in the warm and fertile countryside, that officer exemplifies the now often quoted “banality of evil” Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt (1963) described so incisively to retrospectively make sense of the sheer scale of genocidal coördination the Third Reich needed to accomplish its goal of a perfect Aryan state. The man is somewhat lazy, grasping, self-interested, adulterous, ingratiating — ordinary, just ordinary: the picture of ordinariness in hierarchical middle management — and he and his similar family are fascinating to watch and hear exactly because of that quality.

Glazer and his brilliant cinematographer Łukasz Żal, who won my Pick for cinematography in 2019 for his stellar work on Pawel Pawilowski’s (somewhat patriarchal but still) articulate (2018) Cold War, are smart about this opportunity in the ordinariness of the story; rarely do they let a frame go by without implicating the crisis of atrocities just outside the core of the film’s story. Smoke billowing in the background of a child’s backyard birthday party (as in the image above), ash tainting the running river where the officer casually fishes while his children play nearby, and the silently roaring pulses of the firelight through the evening curtains insist that the characters and their viewers relentlessly confront and consequently either accept or ignore the atrocities just on the other side of the garden wall in order to go on living.

This understated approach to an everyday analysis of the function and reality surrounding a camp like Auschwitz is the film’s greatest strength. Where other films this year saturate themselves and therefore us in their audiences with their indulgences, this film marvels in its eloquent restraint. Choosing specifically when and how to escape in sights or in sounds from the language it’s fluently created to tell its story, The Zone of Interest reminds us in its nomination here that there is still a place for truly excellent cinema at the Academy Awards. Expect it to handily take home at least the Oscars for Sound and for International Feature Film.

As predicted, The Zone of Interest won the 2024 Oscars for Best International Film and Best Sound in addition to the 2024 BAFTAs for Outstanding British Film, Best Film Not in the English Language, and Best Sound and is a Top 5 International Film according to the National Board of Review.

The Zone of Interest is also the 2023 Rich Pick for Directing, Cinematography, Original Score, Sound Mixing, and International Feature.

Temperature check

Steaming

So, that’s my list, readers. Thanks for taking tea with me again this week. ☕️🫖😊 Did any of these films make it into your Top 10 of 2023?

A gay romance — let us not forget, readers — remarkably tinged by the same desperation all its predecessors took as their solemn vows….

Sure, to your conservative aunt who still thinks sodomy is a mortal sin punishable by an eternity in a fiery beyond, All of Us Strangers is kindling set for hellfire; but likely to anyone reading this Substack, trust me, you’ve discussed far queerer.

No, this is not an abdication from directorial responsibility, but the mere consequence of an ambiguously flavored and open-threaded conclusion.